by Claire McNab

Victoria Woodson, a highly regarded associate professor at a Sydney university, is an authority on erotic writing of the Victorian era. Her passion for this literature amply compensates, she believes, for the unfulfilling male relationships she has dropped from her life.

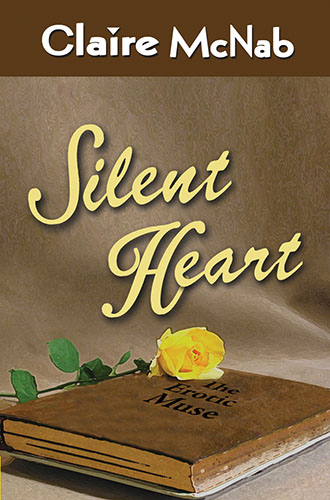

A savvy commercial publisher has pounced on a book Victoria intended for an academic audience. Victoria is shocked and disconcerted to see The Erotic Muse become a world-wide bestseller.

Reyne Kendall, an experienced and award-winning journalist, is assigned to do an in-depth feature on the woman behind the bestseller. Victoria dreads the sort of aggressive, probing person Reyne is likely to be. Her misgivings prove to be more than correct.

Reyne is self-made, irreverent and tough, and has little respect for the cloistered world of academia which is Victoria’s sanctuary. Reyne brings one other volatile ingredient—she is boldly out as a lesbian.

Originally published by Naiad Press 1993.

You must be logged in to post a review.

The water at Circular Quay sparkled in Sydney’s relentless summer light. The Opera House’s huge curved shells looked suitably impressive for any tourist. The waiter slid a plate in front of me with reverent precision. Hugh Oliver of Rampion Press beamed at me across the table, his high color and short sandy hair giving the impression of a mischievous and somewhat overweight schoolboy.

I feigned enthusiasm. “I’m very much looking forward to the States…”

This is what two-thirds of my lunch-time audience wanted to hear. “It’ll be a humdinger of an author tour!” said Hugh with all the enthusiasm appropriate for the head of Rampion’s publicity department. Christie O’Keefe, photographer, nodded affirmation. The third person at the table just looked at me.

I stared back, masking the hostility I felt. Reyne Kendall was a journalist published internationally by Millennium magazine. Hugh Oliver had taken all the credit for organizing the article that was to feature me and, more importantly, my book, The Erotic Muse. He had called me two days ago, his self-satisfied voice booming over the line. “I’m so pleased, Victoria, that the editor has run with my idea…and that he’s going the whole hog. The Millennium article won’t just be a page or two, but an in-depth piece with color photographs in all editions, American and international.” He had then cajoled me into lunch with the photographer and journalist assigned to the story.

So here I was, sitting in a charming restaurant with a stunning view of city and harbor, looking at a woman who, in my normal life, I would never even consider meeting. Reyne Kendall was of average height, strongly built, and even when motionless, had an aura of energy. Her gestures were sudden, definite, her manner disdainful. Her brown hair was enlivened with a hint of red, her eyebrows emphatic, her eyes dark, she had an unexpected dimple when she smiled. When still, her face was solemn, unremarkable, but animation gave her an attractiveness that flared beneath her fair skin.

From our first meeting an hour or so before, she’d been the brash, aggressive journalist I’d expected. Full of opinions, questions, cynical observations, all delivered in a voice that was too loud, too confident. When Hugh had first suggested the luncheon, I’d reviewed the little I knew about the woman and then consigned her to a mental box labeled “journalist-reporter, blunt, ambitious, exploitative.” Up to this point she’d fitted the stereotype, and my initial wariness had ripened into active dislike. I felt justified in my evaluation of her. Now she was unsettling me with her silence, her level stare measuring me dispassionately.

My expression must have shown something, because she said abruptly, “You’ve absolutely no idea what you’re letting yourself in for, Professor.”

I was sure she used my title with irony, as I’d been introduced as Victoria Woodson. Before I could respond, Hugh, predictably, rushed in. “Reyne, I’m sure Victoria has a very clear idea what’s involved—the promotion of a world-wide bestseller!”

“You’ve got a vested interest in making her think it’s a piece of cake.” She turned to me with a sardonic smile. “The first thing you learn is never take anyone in publicity seriously.”

I said lightly, “I try not to take anything too seriously, and that naturally includes Hugh.”

“You surprise me,” said Reyne. “I’d have thought you might tend to take everything rather too seriously.”

My aversion to this woman was healthy—and growing. I turned away from her to say to Christie O’Keefe, “You said you wanted to take a few quick photographs with the Opera House in the background. How about now, while we’re waiting for coffee?”

I was warming to Christie. We had chatted effortlessly through lunch and I appreciated her self-deprecating humor. I also found her air of unfussy competence much more acceptable than Reyne Kendall’s tough reporter persona. Physically, even, Christie was more comfortable. Much shorter than I, she had a pleasant face, pale blonde hair and a slight build. Her taste in clothes tended towards somewhat gaudy primary colors, but she moved with capable economy and impressed me as someone who would always be on time and fulfill her professional duties well.

Leaving Hugh and Reyne debating some trivial matter, Christie and I left the discreet coolness of the restaurant for the strident heat of a summer day. A broad balcony overlooked the busy cove, and while Christie unpacked her well-worn black leather equipment case, I leaned against the railing and contemplated the city. The towers rose, washed by sunlight. A sleek white luxury liner was moored at the International Terminal, ferries hurried to wharfs, the Opera House sat complacent in its bizarre beauty.

“Do you ever wear bright colors?” Christie said as she tried different camera angles.

“Not as a rule. I prefer white, black, navy blue…”

Christie grinned at me. “Hey, that’s great, but as Millennium prints in color, maybe you should consider something that’s—”

“Less plain?” I said, eyeing her brilliant red and yellow overalls.

“Uh huh.” She laughed as she peered from behind the camera. “I wasn’t suggesting the sort of thing I’ve got on—just something in a warm rose, or maybe a lime green.”

I looked down at my white linen skirt and tailored dark blue blouse. Perhaps my taste in clothes was too conservative for someone like Christie, but I felt at ease with my classic style. Wanting to change the subject, I said, “You’ve worked with Reyne Kendall before?”

“Sure have.” Her face alive with amusement, Christie added, “I suspect you two may be evenly matched.”

“Oh, yes?”

“Reyne can be intimidating. I don’t think she realizes the impression she makes.”

I was sure she did, but I nodded affirmatively. Christie squeezed off several quick shots. “And the fact you’re a professor throws her a bit, I think.”

“Why?” I was genuinely puzzled.

“She’s the classic self-made woman—started at the bottom and did it the hard way. Reyne’s got a great track record, learned it all on the job, is suspicious of paper qualifications…”

“Suspicious? She sounds positively paranoid.”

Christie’s smile was indulgent. “I’m sure Reyne admires what you’ve achieved. There’s just no way she’ll ever admit it—to herself or to you.”

“So Ms Kendall doesn’t mellow with longer acquaintance?”

“Mellow? Not a word I’d ever associate with Reyne.” She moved me along the railing, squinted into the viewfinder. “That’s what makes her so good—she’s uncompromising, unsentimental, and almost impossible to fool. She’s done some great investigative journalism. Did you see her series exposing the scandal of international tax shelters?”

“Don’t think I did.”

Christie grinned. “The way The Erotic Muse is selling, maybe you’ll need to study it.”

* * *

After lunch, as I drove back to the university, I considered with apprehension the disturbance to my ordered life that The Erotic Muse had caused. Surely I’d never have agreed to rewriting my academic study if I’d realized what an upheaval it would create…But, then again, there was now a tinge of excitement to each day, and I was vain enough to feel pleasure at the public recognition of my name and the fuss that Rampion Press was making over me.

The reaction of my university colleagues to my sudden notoriety had varied. The Vice Chancellor had tut-tutted, but avoided outright condemnation—what he’d actually said was, “Pity there’s so much actual sex in it, Victoria. Otherwise it’s an admirable study, particularly on the hypocrisy in the establishment.” Those in my own department had run the gamut in their responses—envy, outrage, amusement, approval. No one was indifferent, including my students, whose contributions to tutorials now included considerably more comments about sex and love. With amusement I’d realized that their former perception of me as a dry, remote professor had been replaced by a somewhat spicier academic model. As I waited for a traffic light to change, my gaze idly fell on a newsstand and the latest Millennium magazine. I felt a sudden guilty pride that such an up-market publication would be featuring me. Of course I didn’t really deserve it—all I’d done was take the great themes of love and desire in literature and make them accessible to a wider public. I was quite prepared for it all to be an exciting few months of notoriety, then I would sink back into anonymity again.

As vividly as a photograph, Reyne Kendall jumped into my mind, staring at me with insolent, dark eyes. What did she think of me? Had she read my book and sneered at the thought of an associate professor of English cashing in on the constant human interest in sex?

As I considered my almost immediate dislike for her, I vaguely recalled a psychological explanation for the antipathy I felt—something to do with the idea that you recognize in the other person a characteristic that you yourself have, but don’t accept. That didn’t seem a likely explanation here. Apart from the fact that we were both female, we had nothing else in common. Reyne Kendall was brusque, inquisitive, pushy, whereas I was…

I smiled to myself. The words I would use included logical, reasonable, controlled—yet here I was on a dizzying merry-go-round of appearances and interviews because I had allowed my academic literary treatise to be transformed into a popular success.

My office at the university wasn’t large, but it was neat and well-organized, dominated by an antique desk I’d restored myself, and decorated with a few favorite pictures, mostly etchings of native birds. I opened the door with pleasure, expecting to enjoy the solitude of a few hours of work.

“You’re here at last,” said Zoe from where she stood at the window.

As usual, my cousin started our conversation by pacing impatiently with small, emphatic steps, her high heels digging viciously into the gray-blue carpet. I’d seen her only a few weeks ago, but she’d noticeably put on weight. Zoe was perpetually on some new diet, each embarked upon with religious fervor, then criticized with bitter disappointment when the loss turned out to be temporary.

Ever since I could remember, Zoe had been able to aggravate me by her refusal to sit still, to listen, to be logical. Always an emotional incendiary device, today she was spitting the words out with righteous outrage. “…never considered the family, when you wrote it, did you? Typical of you, Victoria. It’s a good thing Mum’s gone—she’d be sickened to see what you’ve done. And Dad’s past it, thank God.”

“I haven’t done anything. It’s an academic study.”

“Academic?” Zoe always sneered effectively. “It’s called The Erotic Muse, isn’t it? You really think that’s an academic title?”

“My publishers—”

“Your publishers. How can you look anyone here at the university in the eye after the Rampion Press advertising campaign? You can’t approve of the ads! They’re selling sex, it’s simple as that. I don’t know what John thinks, but I…” Her shrug was the distillation of years of displeasure with me, the intruder into her family.

Somehow her antagonism was comfortable. I always knew where I stood with Zoe, having spent my life from age seven learning the rules of the games she played. “I’m sorry if you’re upset, Zoe, but I’m not going to apologize for my book or anything to do with it.”

“You make me ashamed of the Woodson name.”

I was tired of Zoe’s extravagances. “You don’t even have the Woodson name. You changed it when you married Arthur.” I didn’t add a comment on the backflip she’d accomplished to do this from ardent feminist resisting patriarchal social mores to enthusiastic endorser of the status quo.

Mention of her marriage always soothed Zoe. Her tone was more conciliatory as she said, “Don’t suppose you chose the title, anyway.”

Her comment amused me. I remembered the publishing executive’s horror as he exclaimed, “You can’t call it that!” when I made what I thought was a clear concession by condensing the original title, A Study in Carnal Affection in Literature from the Victorian to Modern Times to the snappier Carnal Affection in Literature.

“I didn’t choose the title,” I conceded.

“Suppose it’s already made quite a lot of money?”

“I think it might, eventually.”

She finally sat down, a move I recognized as a bargaining stance. Zoe was nothing if not predictable. Her first move in this phase was always to show a desultory interest in my personal life. “How’s Gerald? You haven’t mentioned him lately.”

“Gerald’s fine.”

“Perhaps you two could come round for dinner one night?”

“Zoe, I don’t think—”

“Don’t tell me you’ve broken up with Gerald! Honestly, Victoria, he’s just perfect for you.”

It was easier to take the path of least resistance. “I’ll see when Gerald’s free and call you, but it won’t be right away. I’ve got this author tour coming up.”

Zoe nodded, satisfied. The preliminaries over, she leaned forward to say earnestly, “You know, Victoria, I must remind you that we are expecting you to invest a little in the family.” When I didn’t respond, Zoe’s lips curled in the charming smile she’d used as a weapon all her life. “Arthur’s business has excellent prospects…”

Arthur St. James was a thoroughly presentable husband for Zoe, but the very thing that attracted her—his malleability—made him a very inefficient businessman. He was talented in computer software development, but lacked the skills to capitalize on his abilities; his little software company constantly trembled on the brink of disaster, saved only by the genuinely innovative product that he had created, however badly he marketed it.

“Zoe, you should understand that there’s a considerable delay before I receive royalties, no matter how well the book is selling.”

“Okay, but when you do get paid, I’d like to think you’ll put money into Arthur’s company.”

“I’ll consider it.”

It used to disconcert me, the way Zoe could change from emotion to emotion, as though a switch had been thrown. Now, I mentally shrugged as she abruptly stood up, her face flooded with instant anger. “We’re family, Victoria. You owe it to me.”

I didn’t ask, “Why you, in particular?” I already knew the answer. Zoe felt she was entitled to reparations. She had been a precocious eight-year-old when I had been thrust into her comfortable world by the death of my parents. To me personally, Zoe had never bothered to hide the bitter resentment she felt towards an orphaned child who had usurped her position as baby of the family. She was more circumspect with others, earning admiration for the loving way she had tried to make her cousin welcome.

I wondered, as I often did, how anyone could choose to live with Zoe, although Arthur seemed content, even happy. Perhaps it was my perception that was at fault—I didn’t see things the way others did. For example, looking back at my childhood with Zoe, John, and my aunt and uncle, I perceived myself as quiet and cooperative, but I could still hear my Aunt Felice, Zoe’s mother, as she repeated her constant observation, “You’re a difficult child, Victoria. Very difficult.” She had never explained what “difficult” might mean, and her tight-lipped austere face ensured that I never asked her.

Strange how someone with such a soft name—Felice—could be so forbidding, so strict. My aunt was well-matched with her husband, an Anglican minister whose God was definitely Old Testament. My memories of him always included his harsh, metallic voice vibrating with righteous anger. Aunt Felice was a much quieter, but even more formidable person, and though she had died some months ago after her second heart attack, to me her presence was still palpable.

I came back to the present with Zoe’s impatient, “Well?”

“I’ll consider it, that’s all I’ll say. And don’t try to make me feel guilty, Zoe, please.”

Zoe had early mastered the ironic impact of one raised eyebrow. “Guilty?” she said, her emphasis making it clear that this would be an appropriate response from me.

Then, abruptly, she was moving towards the door. Zoe always liked to terminate conversations first, whether on the telephone or in person. It used to challenge me to beat her to it, but now it just wasn’t important enough to try. She paused. “I almost forgot. I’ve finally got around to going through some of Mum’s things, and I found some photos you might like to have.”

When she had closed the door behind her, I sat looking at the brown envelope on my desk. I’d never been sentimental, never kept photographs or keepsakes to remember the past. I didn’t believe in looking back.

Reluctantly, I slid out the contents of the envelope. Photographs of me, unsmiling, squinting at the camera. Not one of them taken before I came to my aunt and uncle’s cold home. None of my real mother and father. None of the house near the beach that I’d gone back to as an adult and tried, in vain, to remember as part of my early childhood.

I flicked through the family photographs—Zoe smiling vivaciously at the camera, John taking his status as eldest very seriously, Uncle David stern, his white clerical collar as tight as his mouth, Aunt Felice with her careful smile that never showed her teeth. And me—I felt a pulse of anguish at the face of that little girl, hollow-cheeked, grave, staring stoically out at me.

“You’re so dramatic,” I said to myself as I shuffled the photos together and shoved them back into the envelope, upon which Zoe had written with her impatient scrawl, For Victoria. There was no reason for me to feel any particular sorrow for the little girl who had been me. I could remember only snatches of my life before my aunt and uncle took me in, and from then on it wasn’t unbearable. I wasn’t an emotional child—I didn’t wail and complain, and I was looked after well and given educational opportunities that had eventually led to my present position as Associate Professor of English. Really, I had no grounds for reproach.

But still, that thin face that had been me stayed in my mind.

* * *

I’d asked Gerald for dinner that evening—or rather, he’d maneuvered me until I gave him the invitation. I watched him warily as he opened the wine for dinner, his long thin fingers skillfully manipulating my skittish corkscrew. He looked serious, preoccupied, and I felt a brush of apprehension about what he might want to discuss.

Tao, my sleek Burmese cat, was contemplating us both, his body tucked into a neat parcel with his paws folded under his chest. I stroked delicately between his ears and was rewarded by the sigh of a purr. “Have a good day?” I said to Gerald, introducing a safely neutral topic. If that subject failed, I could always fall back on the weather.

“The usual. Creative excuses why assorted theses are running late, tutorials where the only students who contribute are the ones who’ve done no preparation whatsoever, the customary skirmishes with Admin…” He grinned as the cork came out smoothly. “Pretty much an ordinary day. How about you?”

“Lunch in the City with publisher, photographer and rabid journalist.”

Gerald possessed a deceptively mild appearance. I was accustomed to hearing what a nice man he was, expressed in tones of surprise that implied a professor of history could not normally be expected to have this quality. Nice was too weak a word to describe him—civilized suited him better.

As he poured the wine, he said, “No doubt your publisher was represented by the attentive Hugh Oliver, but who were the others?”

I hadn’t enjoyed lunch, and wanted to forget about it. Equally strongly, I didn’t want Gerald bringing up anything about our relationship. Deciding to skate over the information and then firmly lead us back to a reliable topic, such as university politics, I said, “Both from Millennium magazine. The photographer’s an American woman, Christie O’Keefe. The journo’s Reyne Kendall.”

He surprised me when he said, “Know them both.”

“Indeed? Is Millennium doing a cover story on Gerald Humphries?”

He grinned at my tone. “No, darling, you’re the one the magazine’s profiling, because you’re the one with the sexy bestseller.”

The word “darling” reverberated in the room. I was scrupulous never to use endearments, and his casual use of the term seemed almost to imply ownership.

With his usual care, he settled the wine bottle into its bed of ice in the silver bucket he’d given me for my birthday. “The reason I know Christie O’Keefe is that she collaborated on Penter’s book—she did all those moody photographs to match the moody poems.” Dr. Penter, from the School of Computing Studies, was an officious, bustling man with an astonishing streak of literary ability in him. “And Reyne Kendall’s done some sound work on street kids. Had a lead article a couple of issues ago that I thought was pretty good stuff.”

“I didn’t see it.” I had seen it, but couldn’t bear to read about the misery of abandoned children’s lives.

Gerald was looking at me with a faint smile. “I get the feeling you didn’t warm to Reyne Kendall.”

“She was confronting, pushy. I’m not looking forward to having her tag along to Brisbane and Melbourne.”

“It’s the price of fame, Victoria. You better get used to it, especially when you tour the States.”

“If I tour the States.”

My prevarication didn’t convince him. “You know the university will give you the time off, and you’ll be surprised how quickly you become accustomed to limousines and luxury hotels.”

I sipped my wine. It disturbed my ordered world, but it was exciting—to be caught up in a round of interviews, of people wanting to meet me, speak with me, just because I had written a surprise bestseller. I heard Zoe’s sharp words: “…selling sex, it’s as simple as that.” She had a way of cheapening things I’d achieved, but I refused to feel ashamed of what I’d written.

“Gerald, I know it’s got a catchy title, and I’ve rewritten some of it for the general public, but…”

He touched my hand reassuringly. “Yes, your book’s good, don’t ever have any doubts. Good scholarship and good writing, and we both know those two don’t necessarily go together.” His expression changed. “Talking about going together…”

“I’ll check the oven.”

He followed me into the kitchen. “We need to talk about us.”

I tried to speak lightly. “No we don’t. Everything’s fine.”

“It isn’t fine for me.”

I felt trapped, smothered by his demanding affection. Allowing anger to defend me, I said sharply, “What more do you want? You’ve got a companion, a colleague, a bedmate. You’re not going to ask me to wash your socks, are you?”

He put his hands on my shoulders. “I want a commitment.”

“Oh, come on!”

“Don’t dismiss what I’m saying without thinking about it, Victoria. It’s what we both need—a permanent relationship.”

I had thought about it, long and hard. Keeping my voice level, I said, “I don’t need it, Gerald. And if it’s a condition of us staying together…”

His short laugh was bitter. “Staying together? We’re not together in any way I accept. So, we spend time with each other, we go to bed fairly regularly…in your terms that’s a relationship, is it?”

“I’ve got to serve dinner.”

Taking the chicken out of the oven gave me an excuse to avoid his accusing gaze, but his tone slapped me. “Jesus, Victoria! How do I get through to you? I care for you but I don’t think you love anyone, not even yourself.”

Fury made my voice thick. “Remember history’s your forte, Gerald, not psychoanalysis.”

He leaned back against the kitchen bench and folded his arms. “Since you’ve brought it up, why not consider therapy?”

I stared at him. “Therapy? Me? You’ve got to be joking!”

His face was flushed with anger, but he kept his voice level. “Don’t just refuse to consider the idea. It could give you some insight—”

“Into what? Your delicate male ego?”

“How many relationships have you had, Victoria, before me? I’m the last of a long line of men, and you’ve dropped every one of us the moment things got too intense. I think you’ve got a problem.”

“I have. It’s you.” I wasn’t afraid of other people’s anger, but my own rage terrified me. I took a deep breath. “I don’t want to talk about this.”

“We have to.”

I wanted to smash something—a plate, a glass, his concerned face. “Gerald, please go.”

He was astonished. “Go? But we…”

“Take the chicken with you, if you’re hungry,” I said with bitter humor. “But leave, right now.”

He closed the door behind him very gently, as I knew he would. I looked around the room, relief spiraling through me. Relief that I didn’t have to go through the motions of a relationship. And, though I shied away from the thought, relief that I didn’t have to share my bed tonight.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.