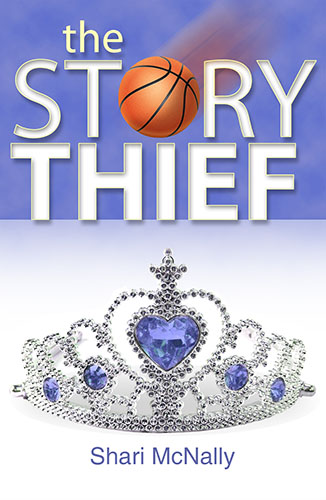

by Shari McNally

High school. Where every girl lives the same story, over and over. (Cinder) Ella Armstrong has tried to fit into other people’s stories. It doesn’t work. But her own story, the one where she’s courting a princess and not a prince, is way too weird to tell.

There are some things you just can’t help. When the school Rebel Queen Renee Hammond needs a knight, Ella dumps the idea of glass slippers and takes up the challenge. Worshipping from the sidelines works for her—until good girl Diane Lacey makes Ella yearn to write a new story for herself. A story where the girl might get the girl, but most of all, the girl gets herself.

Newcomer Shari McNally creates an engaging world where a young woman finds she must steal her own story or others will write it for her.

GCLS Goldie Awards

The Story Thief — Finalist, Lesbian Debut Fiction.

You must be logged in to post a review.

I met the Rebel Queen in 1975, the first week of our freshman year. She was playing volleyball in the girls’ gym. I sat in the bleachers and watched the junior varsity team run through drills—serve, set up, spike. I don’t remember why I was there. A schedule screwup? I really can’t remember. What I do recall is her wearing a loose-fitting sweatshirt and tight shorts that showed off the long stringy muscles in her legs. I can remember the wickedness of her beauty, the way it mocked those around her. And her long blond hair, beyond straight it was so straight, like a beacon in the dark. She was light and everyone else was shadow.

When the bell rang the Queen walked over to where I was sitting and introduced herself with brown shiny eyes that made me think of hard candy, the flavor of root beer.

“Renee Hammond.” She extended her hand.

I had never, in my whole life, been offered someone’s hand to shake. I took her hand and shook it, awkwardly, loosely, like a rag doll. “Ella Armstrong.”

“Ella? So you’re Cinderella? I knew there was something different about you. I’ve read your story, you know.”

I’d never had anyone that I didn’t know from a young age guess my true name. Everyone always accepted Ella without question. I couldn’t speak. I wanted to tell her not to call me that, but I couldn’t. All I could say was, “That’s not my story.”

* * *

My mother had glass slippers made on my sixth birthday. I remember her face when I unwrapped them. She smiled at me with a gluttonous hunger and said, “For my beautiful princess.”

I tried to walk in them, but they didn’t bend. I could only shuffle. My father was annoyed. He was watching football. “She can’t wear those. It’s a story. You can’t walk in something made of glass.”

“What do you care?” my mother snapped back and the daily fight began. “You can’t stop watching football long enough to celebrate your only child’s birthday.”

I tuned out my parents’ fighting and wandered out of the room. The slippers hurt my feet, but I didn’t dare take them off. My mother’s happiness was so fleeting and fragile, I did whatever I could to make it last.

I didn’t really think about what I was going to do as much as I felt what I was going to do. I wandered into my parents’ room and looked up at my father’s sword collection. I unhooked the lowest one and held the weighty length of it in my hands. Once unsheathed, the sword was much lighter. I could hold it with two hands and make it slice through the air. I stood in front of the full-length mirror and posed in a warrior fashion. Now the outfit was complete. The party dress and petticoat, with the glass slippers, were set off perfectly with the glint of the blade. I swung the sword through the air, slicing all evil to shreds, vanquishing all nightmares, until only the good remained, protected by me, the chivalrous Cinderella.

I didn’t see my mother enter the room behind me. When she screamed my name, I naturally swung around. I didn’t feel the blade strike her as much as I felt the blade stop wobbling in my hands—the contact created stillness, a terrible steadiness. I dropped the sword and the hilt landed on one of my glass slippers, shattering it.

My mother grabbed her thigh and stared at me with her mouth open, but unspeaking, and I saw the blood soak through the material of her knock-off Jackie Kennedy Chanel dress, down her thigh and past her knee. She looked at me carefully, her eyes taking in my dress, looking down at my shattered glass slipper before moving on to the sword. There and then, that was when her eyes changed. When her eyes met mine again, they left me forever. In that moment, my mother was gone from me, from our home, even as she still stood there in front of me.

My father rushed into the room and everything after that was a blur, the bloody rags, the hospital, the thirteen stitches my mother needed on her thigh, the lecture my father received in the emergency room about displaying weapons within the reach of a child.

I apologized over and over again to my mother, in every way I could think of—softly, loudly, dramatically, sincerely. I positioned myself in front of her, held her hand, wrapped my arms around her, but nothing I did could persuade her to look at me.

I disappeared. I was dead. A ghost. She could no longer see me.

The next day, when I came home from school she was gone. My father was sitting on the couch, the same spot he always sat in, holding the remaining glass slipper, doing his best to explain the inexplicable. “I’m sorry, Cinderella, but your mother isn’t quite right. This has nothing to do with you. It isn’t your fault.”

I was young, but I wasn’t stupid. I knew I wasn’t what she wanted me to be, and that’s why she left. I grabbed the glass slipper from my father’s hands and threw it at the wall. It shattered so easily it was as if it was destined to shatter, as though it was waiting patiently to be put it out of its misery. “Don’t ever, ever, ever call me Cinderella, ever again.”

* * *

When the Queen asked me to go to break with her and get a Coke, I was surprised. I don’t know why she asked, and I don’t know why I accepted, since we’d never set eyes on each other before. But this is the way stories happen when you’re young. There are no preconditions or pretexts necessary, unlike the adult years where all meetings are weighed down with the necessity of cause and reason.

We connected right away—in that way that makes you feel like something really right is happening—and that afternoon we went to her house, to her art studio/bedroom, and I saw her paintings. She was an artist, and her paintings were vivid and brilliant, primary colors that demanded attention. It became my lasting impression of Renee: vivid, brilliant, primary.

We became best friends, not slow and sure, but in an explosive event.

It was the beginning of my life as a new character, detached and removed from the Cinderella story of my parents.

It was Renee who woke me up, pried my eyes open, and made me see life for what it was—a chosen narration—and she was the ray of light that would carry me through that perilous story to the end. I was now Cinderella, Knight to the Queen.

Anarchy

1978

Close to the beginning of our senior year, Renee orchestrated the painting of a mural. It was a sneaky midnight art attack—as usual, outrageous and politically driven—painted on the side of the high school administration building. It was the Rebel Queen’s fourth art attack. Previous murals included covering an outside wall of both gyms and the cafeteria. Her current high school record now showed two suspensions and, to add insult to injury, the murals were painted over each time. She and Principal Monroe were at war over the so-called art. He saw her creation as vandalism and she saw his response as censorship.

Renee had worked all night. The mural was littered with abandoned cars, odd and even numbers scrawled upon them. It represented the odd-even system of gas rationing (if your license plate was odd-number you filled up your gas tank on odd-numbered days of the month, while even-numbered plates were only allowed to fuel on even-numbered dates) and it spoke to the fucked-up order of things. There was a scathing commentary on California’s Proposition 13 and the school programs it axed while saving our parents from high property taxes. The summer session would be literally extinct now and Renee memorialized the losses from basketball classes to drivers education. She painted a not-so-flattering picture of Howard Jarvis and Paul Gann, the architects of the proposition that would bleed our schools dry. Included were lyrics from The Runaways, The Sex Pistols, and Patti Smith. She orchestrated the project, creating the core sketch, and other kids from her art class helped with the painting. The other arties were never caught because Renee made them leave before dawn. But Renee, as their leader, was interrogated each time and suspended. She wouldn’t name names and never allowed anyone to take the fall with her. Still, not one of her fellow arties ever stepped forward.

Everyone else went home a few hours before dawn. Renee was left, finishing it up, and Patty was acting as lookout. I came early to help with the clean-up. I wasn’t talented enough to actually help with the painting so I was hiding paintbrushes and other incriminating articles in my locker when I saw Patty running toward me. I knew something wasn’t right by the disastrous look on her face. Her hot iron Farrah Fawcett curls drooped around her face as testament to the long night.

“Ella, they caught Renee! They just dragged her off to Monroe’s office.”

“No way!” I slammed my locker shut. “Who would be here this early?”

“Mrs. DeBurgh. Figures that weirdo would come to school early. I mean, really, does she even have a life at all?” Patty huffed while trying to pat her curls back into place.

Mrs. DeBurgh was the history teacher. Her husband died two years ago and she wore his clothes every day. Every day she taught in her dead husband’s clothes, and they hung on her as if she were a child playing dress up. Most people made fun of her, but I always felt a little sorry for her. Maybe other people felt that way too, but they didn’t show it. I was always a little nauseous when I was in her class. Her despair made me feel claustrophobic. I couldn’t distance myself from it, and it emanated from her like cheap cologne that threatened to suffocate us all.

I imagined Renee, quite contained in her capture, not letting on in the least that it shook her, climbing down from the ladder, paintbrush in her teeth, to see Mrs. DeBurgh waiting for her. She probably chastised Renee repeatedly, searching for some signs of remorse between pulling her too-big trousers up higher so she could walk Renee to her punishment.

“How long until first period?” I asked.

Patty looked at her Lady and the Tramp watch. “Another hour and a half.”

“Shit.” I paced and shoved my fists into the shallow pockets of my skintight jeans. I felt Patty’s eyes on me. “Okay, I have a really far-out fucking idea.”

We ran around to the front of the school to where Principal Monroe’s office was located. Patty hung back as the lookout (a role that she was relegated to regularly) as I pushed my way through the bushes to peek inside the window. The room was dark and it was hard to see anything, only Monroe’s desk and the closed door. In the corner, on the floor, I spotted my Rebel Queen. Her knees were pulled up to her chin and her arms were draped across them, her forever-determined chin resting on her forearms.

I tapped on the window. She turned and looked in my direction like she had grown bored waiting for me. A pair of pitch-black Vuarnet sunglasses shielded her soft brown eyes. She was always hiding the softness of her eyes behind a pair of sunglasses.

Renee got up off the floor and walked to the window. It was old and all she had to do was turn the lock and slide it up. I know Renee, she did this purposefully slow. Once it was open, she pushed the black frames back, scooping up blond hair as she did so. She leaned on the ledge to tease me. “Come to my rescue, have you? So dependable, my loyal Cinderella.”

She knew she was the only one I allowed to get away with calling me that. Anyone else would have been punched in the nose.

“Fine by me, I’ll leave you here to rot.” I turned and walked back through the bushes.

“You? The pure of heart? My loyalist knight? Ella Armstrong, you get your ass back here!”

The thrill of her voice firmly saying my full name stopped me in my tracks. I turned, but held myself cool and composed. “And why should I help an ungrateful bitch like you?” The hint of a smile curled at the corner of my mouth.

An unexpected laugh was bestowed upon me, the loyal knight, but it turned into a pout almost as quickly. “Seriously babe, what am I going to do? My parents are going to shit.”

I walked back to the window and put my hand on her arm. “I have a plan. Just sit tight. And don’t ask me what it is—you’ll ruin the surprise.”

Renee dropped her head below her shoulders, shaking it over my nerve. But it was my win. I’d gained her confidence. “Okay, fine, don’t tell me, but may I remind you it’s my ass on the line?”

“Just hold on to your ass ’cause I’m going to blow this place sky-high.”

“No shit?” She chuckled, not believing a word I said.

“Sure am, all you have to do is sit pretty and go along for the ride.”

She put her hand over mine. “We both know you’re always my best shot at liberation.” With a lopsided smile, she added, “You always have been.”

“Foxy and a flatterer. Will wonders never cease?”

She didn’t lose her smile as she walked back to the corner. She sat down and pulled her legs into her chest. She was a mystery to me. Sometimes as mighty as a giant, other times as delicate and fragile as a china figurine, as she seemed to me now.

I made my way through the bushes, taking the ANARCHY button off my shirt, along with the other half-dozen buttons that marked me as anything less than good girl. “Come on, chick,” I told Patty. “We have some phone calls to make.”

* * *

I watched my plan unfold as the cameraman panned to get a full shot of the mural. A prettied-up woman reporter talked to him, while another less beautiful print journalist talked to the students gathered around the painting, his photojournalist vying for space with the roving cameraman. By then the news had spread and there wasn’t a single student in class, every one of them trying to figure out how to get on TV.

I’d snagged the local paper, but my big score was getting the local television station from Los Angeles to make the dull trek through the San Fernando Valley, over the hills, to the Mojave Desert, the embarrassing stepchild of Los Angeles County. LA didn’t know we existed until October 1977, when the space shuttle Enterprise landed at the Mojave Desert’s Edwards Air Force Base. I’ve always wondered if that was part of the reason they agreed to cover the story. We were, for a brief moment in time, interesting. I hooked the press with the promise of radical politics, juicy censorship, and thrilling student protests against Proposition 13.

Monroe came out of his office with various teachers following behind. He was trying to be casual about the reporters and the students going wild trying to get on camera, but nervous red blotches covered his face. When the plastic woman reporter approached with her polished nails glistening like the claws of a predator, Monroe shook her hand like a zebra in a pack of hyenas.

“We received a call about this wonderful mural,” she practically crooned, “and wondered if we might talk with you and some of the artists? Bobby,” she called over her cameraman. “Let’s get this shot set up.” While the reporter was busy setting up her shot, the print journalist saw Monroe and ambled over, a look of weariness on his face. He fired questions at the principal. “This anti-Prop 13 mural is very admirable considering it won’t be popular with many parents who approve of the property tax protection that Prop 13 provides. What was the process of allowing the students to have a voice about something that so clearly impacts their education, and whose idea was this—a teacher’s, a student’s, or does it represent the school administration’s stance?”

“Well, I, uh,” Monroe stuttered.

I gave Patty a shove forward and she took her cue. “It was Renee’s idea,” she said.

The reporter turned to look at Patty—his new source of information. “Can I get a last name?” he asked.

“Hammond. She thought up the whole mural idea, including the theme, but she never could have pulled it off without the help of Principal Monroe. He’s been so supportive and generous with his time.” Patty smiled sweetly at Monroe and batted her eyes at him.

The reporter looked at Patty suspiciously. “When the call came in, we were told this was a controversial situation—a case of censorship. If your principal isn’t censoring you, who is?”

Patty waved my hook to the press away with one dismissive hand gesture. “Oh no, not on Principal Monroe’s part. But this poor man, the student’s hero, has to do battle with the school board, parents, PTA mothers…I mean, really, he’s the most popular principal in the history of the school. Everyone loves Principal Monroe!”

I clapped my hands together firmly, shaking my head in emotion. I motioned for the students around me to join in.

Mrs. DeBurgh came forward and eyed Monroe. “But Principal Monroe, I was under the impression you knew nothing about this!”

“I, uh, well…the thing is…” Monroe continued to babble.

“What? Not know?” Patty was incredulous. “He’s been the very foundation of this project. As a matter of fact, he was only keeping it from the rest of the school as a surprise.” That might have been pushing it.

The reporters and DeBurgh looked at Monroe. Patty’s face was immobilized in a smile. I wasn’t sure how much longer she could endure it.

Monroe finally broke and laughed nervously—not confirming it, but not denying it.

The reporter nodded and wrote that down on his pad.

Mrs. DeBurgh looked at Monroe with disdain, pulled up her oversized trousers and wandered off, mumbling to herself.

“Can we get an interview with the artist?” the TV reporter asked.

“Yes, can we talk with her please?” asked the print journalist.

“Sure,” Monroe said, “I’ll go get her, I know just where she is.” Monroe laughed nervously some more. He seemed more like a self-conscious teen than the kids who surrounded him.

Moments later, Monroe walked out escorting Renee by the elbow. Renee pulled her arm away from him but he just took it again rather firmly with a pained smile and whispered something in her ear. The reporters gathered around her but didn’t say anything at first. Stunned by her looks, most likely. Her fair skin and blond hair swam in a sea of black clothing. Her girl-next-door looks with her pretty blond hair, as it streamed down her coat to the middle of her back, warred with the dark clothing and darker attitude. Her black boots and leather pants, Sex Pistols T-shirt, the safety pin hanging from her ear, made her look a little too much like the teenage badass that all adults feared worshipped Satan. In theory everyone wanted to root for the bad girl, but only as an ideal. And unlike the cutesy version of good-girl-turned-bad-girl that was Olivia Newton John this summer in the movie Grease, Renee was the real deal. And no one, most especially an adult, was keen on experiencing the actual physical reality of that ideal in the flesh.

As the reporters asked her questions, I leaned against the wall and soaked up the visual before me. They—the reporters, the teachers, Monroe, the kids standing around—were all so animated. But the Rebel Queen, she just stood there with an expression like the Mona Lisa. I wondered if any of this meant anything to her. This coup was due to her mural and her dogged persistence. Did it make her happy? Sad?

She looked in my direction. I couldn’t see her eyes, under those dark Vuarnet sunglasses, but I knew she was looking at me because she smirked.

The Queen’s Court

We were watching second period action of the boys’ playoffs. Now, watching basketball is not something I’m usually inclined to do, but Patty whined and pouted until Renee and I both agreed to go.

The bleachers were half full with people watching the game and half full with people talking among themselves. It was a meeting place for socializing and people watching. That accounted for all the activity off the court. Half the time you couldn’t see the game because someone was standing or walking in front of you—headed for the snack bar, the bathroom, catching the attention of a friend who just arrived. Even the people who came specifically to watch the game would often give up and give in to the chatter.

Ricky Hernandez had his arm around me. I stole a glance at his profile. He had sharp features that framed the smooth lines of his face. I looked on my other side where Renee coolly leaned back against the next row of benches. Next to her was Patty, who sported the quintessential look from the JC Penney catalogue. She leaned forward watching every move Paul Rand made on the basketball court. Every time he moved her eyes moved with him. The girl was caressing his body from afar.

“Patty, your eyes are gonna pop out of your head,” I observed.

She rested her chin in her hand and never took her eyes off him. “Isn’t he a stone-cold fox?”

I shrugged. Paul Rand was gorgeous if you liked perfection, but I liked bumps and quirks. Give me an all out superb bod and I’ll raise my brow and whistle, but give me someone with a crooked nose, too full lips, some cute physical imperfection, then you’ve got me. My heart thuds faster and I’m much more likely to fall in love.

Ricky Hernandez’s features were too angular for a model’s, but he made me feel safe when I looked at him. He was quiet, rarely said a word, and I liked that.

“Oh God!” Patty bemoaned. “I have to go to the dance with him! I want to get my hands on that cute little ass! Can you imagine him in a pair of Angel Flights?”

“Patty, do shut up already. It’s getting old.” Renee said it wearily, not even bothering to look at her. The antithesis of Patty and her love for disco clothing, such as the Angel Flight pants the boys wore out to the disco, Renee wore punk clothing, plaid tartan bondage pants and self-made T-shirts from her silkscreen classes. Safety pins, buckles and straps all figured prominently. I leaned toward Renee’s style but couldn’t be bothered to go out of the way for the look as she did. I often wore self-made shirts and jerseys, but I was lazy with my pants and often just wore the same ripped up jeans.

Patty sat back, her spirit broken. It was always like this when Renee chastised her for being too exuberant. She looked up to Renee, not that she wanted to be like her (I don’t think anyone, including Patty, could imagine that) but because Renee was something Patty would never be—cool and aloof. The problem was that Patty believed that Renee’s ways were superior to hers. And so she gave in. Always.

And that was high school in a nutshell. The broken, angry, hurt kids were too afraid to show their emotions. That’s what cool was all about. And because they had little regard for their lives they were risk takers—they became the trendsetters, deciding in their reckless way what would be cool and what would not. And all the kids with the functional family lives, with safety, love, support, would follow their damaged peers off the cliff to their respective ruin. This seemed so obvious to me. Patty was the only functional one in our group, but she still tried to be like us. She never seemed to realize we were like that because we were trying to survive.

“Has Monroe said anything to you about the mural?” I leaned back next to Renee.

“He hasn’t spoken to me since The Incident.” She spoke as though fiendish organ music accompanied her words.

“So, does this mean he’s not going to suspend you?”

“I guess there’s a first time for everything.”

“It’s been nearly a month. One of your murals has never been up for that long.”

Renee sighed. “I know.” She sucked on her top lip and looked a little worried, but in moments her expression changed to amusement. She pointed to the floor of the gymnasium and chuckled. “Look at Chad Walker trying to impress our dear Rapunzel.”

She meant Diane Lacey. There was a time-out on the court and Chad Walker was waving and smiling to Diane Lacey, until the coach popped him in the back of the head. I saw Diane among the cheerleaders and seeing her there with them, I thought what I always did: it didn’t make sense. She wasn’t like the others. Patty, with all her exuberance, would have made a better cheerleader than Diane.

Diane was remote, her smile to the crowd almost apologetic. But even so she seemed to belong there—maybe because she was so beautiful, simply the most beautiful girl in the school. Not like Paul Rand was beautiful—all perfect—but, well, I guess she was inner beautiful. Though she was pretty on the outside, what with her wavy brown hair and an all-American smile, it was Diane Lacey’s ways, her difference from others that made the entire school worship her. Unfortunately for her, it was that same difference that kept most people at a distance. Something about Diane was too good, too modest, too 1950s sitcom good girl, and it made people nervous and awkward around her. Maybe it was because she came from such a strict family. She was never allowed to go anywhere except for school. No one really ever got to know her. That’s why Renee called her Rapunzel.

“You know,” Renee said, “Walker’s the only guy who’s ever had the courage to go after Lacey.”

I watched Chad strut and prance about the basketball court for Diane. I watched Diane not know he was alive. “I guess he’s a pretty talented athlete.” I couldn’t think of anything nicer to say.

“All that God-given talent and he’s still just another dipshit,” Renee deadpanned.

It was true. Chad Walker was undoubtedly the biggest jerk I’d ever met. I laughed but came up short when I saw Larry Altman and Gerrard Daniels sit down behind Renee and Patty.

Renee looked at Altman and sat up stiffly. “Where the hell have you been?”

He tried to kiss her cheek but she pulled away as he laughed. “I was with Gerrard. Right, Gerrard?”

Gerrard looked uncomfortable and didn’t answer. It didn’t matter because Renee didn’t even look at him—it was beneath her dignity.

“I don’t give a fuck,” she said under her breath, “if you say you’re going to meet me—then do it! Otherwise, don’t waste my time.”

“Sweetheart!” Altman acted victimized, placing a hand over his wounded heart. “I just lost track of time!”

I turned to look at Altman and his big, bulky, football self. He was one of the few guys in school who could actually grow thick sideburns, and there right below on his neck was a red lipstick mark. I looked at Renee’s naked lips, then back at his muscular neck.

“Hey, Altman, looks like something’s made a nasty bite on your neck.” I gave him my best leveling glare.

His eyes narrowed and a slow smile formed on his lips. “You know, Ella, I did feel something bite my neck, just a few minutes ago, on my way over here. Some foxy little bug must have found me irresistible.” He took the collar of his “I’m too cool” suede jacket and wiped the lipstick away, never taking his eyes from mine.

“Really? Well, if I were you, I’d start wearing turtlenecks. It’s mosquito season, you know, and you wouldn’t want to catch any diseases.”

“What the hell are you two talking about?” Renee looked at me with eyes that were one-part hurt and one-part annoyed.

“Nothing.” I could feel Altman’s eyes burning a hole in my back. I soothed my anger by telling myself that one day I would catch him at his game.

Why they were even a couple was beyond me. Altman was mister jock, mister look at my cool sideburns and my tight bellbottom pants. What was Renee thinking? I know she didn’t give a shit that he was popular. So what the hell did she like about him? He was charming, but so obviously an asshole and a player. I swear he thought a spotlight followed him wherever he went and the entire world was his audience.

“No, Gerrard!” Patty lowered her voice, “I don’t want to go out! I’ve said no a million times! What do I have to do, hire a plane and write it in the sky? Look, I don’t want to be a bitch, but how many times can I say no?”

We all looked at Gerrard. I thought sure he’d crawl into himself. Christ, I would have. For a moment he looked embarrassed but then he leaned forward and whispered to Patty, loud enough for us to hear, “Your voice says no, babe, but your eyes say yes. You know, I can only wait so long before my interest wanders elsewhere.”

I don’t know if Gerrard was saving face, or if he was suicidal and didn’t have the nerve to do it himself.

Patty’s hand balled into a fist and her face turned red with anger. Renee put her hand over Patty’s fist and turned to Altman, imploring him for assistance. But Altman, his chest and shoulders heaving in repressed laughter, was no help.

I looked at Ricky but he simply rolled his eyes and shook his head.

Renee pressed forward, her face just inches from Gerrard’s. “Take a fucking hike little boy. You catch my drift?”

In school, you can be in the same space with someone hundreds of times and never actually speak to him or her. I don’t think Renee had ever spoken directly to Gerrard before that moment.

Gerrard stood, a little too macho for his small frame, and touched Patty on the shoulder. “Let me know when you change your mind. I can’t wait forever. Later, babe.”

I suppose it was a matter of pride.

Gerrard edged his way to the aisle and Altman laughed out loud and threw a paper cup at him. He called him an idiot, in that way boys have of savoring other boys’ screw-ups.

The buzzer rang and it was halftime. The crowd stood up and the cheerleaders ran to a box filled with small rubber basketballs. They started throwing them up into the stands. People were diving for them, laughing as the balls whizzed past them barely out of reach.

I stood there, not really expecting to catch one, when I saw Diane Lacey smile at me. I smiled back, and when I did, she threw one right into my hands.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.