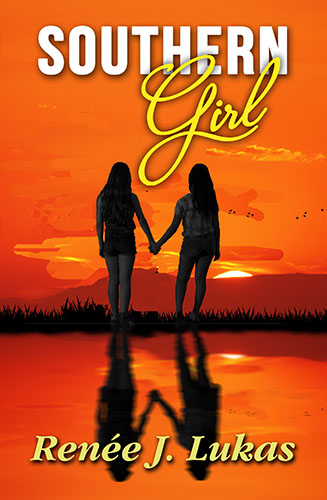

by Renee J. Lukas

Growing up in the 70s and 80s in Tennessee leaves Jesse Aimes confused about pretty much everything. Nothing makes sense to her at all. Not bell-bottoms or crazy teachers and especially not boys. But when she finally wins a spot on the high school basketball team, she begins to feel comfortable in her own skin.

Then her childhood best friend Stephanie comes back to town and stirs feelings in Jesse that leave her even more confused. She knows those feelings must be wrong. She only has to listen to the “you’re going to hell” sermons by her preacher father to know it.

But romance secretly blossoms between the two girls…until their secret is blown wide open by a jealous classmate. As the truth comes out it threatens everything—Jesse’s future in basketball, her family and even her relationship with Stephanie. What can she do when there seems to be no way out?

The Lesbian Review

This is a poignant, beautiful, sad, sweet coming-of-age story about a girl who grows up in a time and place where she is seen as odd and unnatural. It left me feeling like I had just lived her life.

Rainbow Book Reviews

This is a classic tale of a young woman's journey, from an early age, in discovering and accepting her lesbian identity. The romance part of the book is delightful; Jesse and Stephanie are just so right for each other, despite all the obstacles they have to overcome to be together. The historical setting comes across as authentic and accurate, as does the geographical setting of small-town southern America with its strongly religious roots and intolerance of anything different from "normal". There's a smooth flow to this book, as well as excellent story-crafting that had me gripped and reading it through in only two sittings. Highly recommended.

You must be logged in to post a review.

This is it, she thought, traveling down I-40—this is what hell feels like. Tennessee in the summer. No water. No convenience store for a cold beverage. If it weren’t for the occasional highway sign, it could have been Death Valley. As long as she didn’t see any human skulls frying in the sun, she could handle it.

Carolyn Aimes watched fir trees turn to poplars, skyscrapers morph into squatty old barns with rusty roofs leaning precariously to one side, New England light into a southern summer haze. The barrenness stretched out for miles in every direction, giving her the feeling that she and her new husband were the only people left on earth. They were driving to Dan’s hometown, turning off the highway and making their way down unpaved roads that seemed to have been forgotten by every road atlas. It wasn’t long before they were bouncing along dirt roads in the tan Plymouth Duster, not the sporty kind but the tamer sedan style without the racecar stripe on the side, a car conservative and modest enough to meet with Dan’s approval.

Dan Aimes was the only man she’d ever given a second look, and for that reason alone, she had decided to marry him. She’d never been to Tennessee, but she would do everything she could to make a good home and life with him there.

He’d try to make her feel at home, she knew, offering a pat on the knee or a placating gaze, but the expression made her uneasy; it felt insincere. It was a look she called his “preacher face,” familiar to her ever since she’d seen him in action at a religious conference in Boston. Carolyn wasn’t particularly religious. She’d stumbled onto his sermon quite by accident as he was speaking to an outdoor crowd near Faneuil Hall. She had been captivated by his passion and conviction, because she herself had doubts about the existence of God. She stood in the square, holding a shopping bag in each hand, feeling as though he was speaking directly to her. Even more striking was the way Dan spoke—not like every other preacher with the typical inflections. He came across as almost subdued, then the moment you felt lulled into a peaceful state, he’d slam you between the eyes with a sharp, sudden outcry that got everyone’s attention and could very well have been dangerous to those with heart conditions.

He was so obviously talented as a speaker, he almost convinced Carolyn there was someone up in the sky who really cared what she did. It gave her a sense of comfort. Maybe she wasn’t alone in the world. Maybe things didn’t happen randomly, and each person had a path and a purpose. When his speech was done, he came over to talk to her. She was too busy blushing and trying to seem sophisticated to remember a word he said. But they were talking, and, before she knew it, she was giving him a tour of her city.

Back in the Plymouth Duster…

“We should take a bathroom break,” Dan said.

“I don’t have to go.” Carolyn stared ahead with steely determination. She’d never left home before, and she told herself that this was what it meant to be a grown-up. She’d been told she was a beautiful woman. When she spoke, she sounded like Jacqueline Kennedy. She resembled her too, with flawless features and jet-black hair styled in a sixties perm.

But today, as she dug her nails into the vinyl armrests, she lacked the confidence of a Kennedy. She missed her mother, Rose, a no-nonsense, hearty soul who still lived in Boston. After Carolyn’s father died, Rose had moved into a smaller, cottage-style home where she was surrounded by her good friends. She would never leave, Carolyn knew. She would have to be the one to go home to visit her mother, because Rose’s one experience with the South, a vacation just after the war, hadn’t been a pleasant one. Being in the South, she told Carolyn, was like being in a foreign country where no one understood her. She had asked for tonic in a store, and the clerk had brought her a bottle of what looked like medicine. She warned Carolyn to use the word “soda” if she wanted something to drink or she might accidentally get poisoned.

Carolyn’s mother’s admonitions still rang in her head. Rose was an encyclopedia of worst-case scenarios, and Carolyn knew she had to put these out of her mind if she was going to survive here.

Rugged back roads wound through what reminded her of scenes from The Grapes of Wrath—dusty and mostly flat all the way to the horizon. What had she gotten herself into?

“There aren’t any stops now for the rest of the way,” Dan said casually.

Carolyn filled with alarm. What if she had to pee?

An hour later…

“How much farther?” she asked in rising panic.

“Oh, it’s just up a ways.” Dan had a drawl like a slowly grazing cow. It was pleasing to the ear, making him the most popular preacher in the town where they would live. “Just up a ways,” Carolyn would come to understand, meant it could be half an hour. Or three hours. It was his way of minimizing everything, because, as he often said, nothing in this life was as important as the afterlife anyway. Carolyn, on the other hand, had a more practical outlook, because it was in this life that she might be needing to pee. For a woman who had been brought up to be ladylike at all times, the thought of squatting by the side of the road to pee behind some bushes was unthinkable.

Dan gave her hand a squeeze, and she took him in with one glance. His hair was combed in a style that was a decade out of date, with a shock of brown, which was almost the color of the car, parted and greased over to one side, and he wore black-rimmed, Buddy Holly glasses, a plain button-down shirt and brown polyester pants. She certainly hadn’t married him for his sense of style.

“It’ll be okay, hon,” he said.

“Oh, I’m fine,” she lied.

“A little music might be nice.” He turned on the radio, and they were promptly assaulted with news reports about Vietnam. He switched it off.

She sighed, glancing around, hoping to see something, anything, new on the horizon.

Nearly two hours later, they entered Greens Fork, Tennessee. An old Gulf gas station with peeling paint on the roof greeted them first, followed by a country store resembling a log cabin, and one main street, where the bank and some stores drew a few extra cars.

“Let’s try some fresh air,” Dan urged, rolling down his window.

Silently cursing him for shutting off the air conditioning, she dutifully rolled down her window too. Immediately, soaking wet air flooded in, making her blouse stick to her skin. She slapped at a mosquito feasting on her forearm, quietly regretting her decision to move here.

It wasn’t long before street signs gave way to gravel roads, and the car rocked violently back and forth over each pothole, some of them quite deep. The roads were terrible—Carolyn felt as though her internal organs were being rearranged with each bump. They passed a handmade sign that said something about free corn, but all the jostling in the car made it hard to read.

Greens Fork wasn’t exactly on the map; it was the kind of town you stumbled onto while trying to get to someplace better. But a few thousand people called it home, including Dan, who had been born and raised there. That, to her, made Greens Fork far more special than any other one-horse, or one-gas station, town.

Dan’s father had been the town’s beloved preacher for decades until he died suddenly of a heart attack. Dan had always wanted to follow in his father’s footsteps, and when the news about his father spread around town, the people rallied around him, despite his youth. Dan’s natural talent as a preacher and his personal circumstances made him the obvious choice to be his father’s successor. Added to this, when Dan was only ten years old, his mother had left him and his father. Since then, he had been regarded as a poor orphan boy whose mother had cruelly abandoned him. Her flight in the dead of night was judged by the town to be the ultimate betrayal and Dan’s forgiveness of her was viewed as an almost divine act, another reason he was believed to be destined for the pulpit.

The public perception of his mother wasn’t exactly the truth, Dan had told Carolyn. His father’s drinking had gotten worse, and she decided she couldn’t take any more.

“Why didn’t she take you with her?” Carolyn had asked.

“I’m not sure she really had it in her to be a mother.” He was resigned about it, as if there were no emotional scars left. Everything was sewn up neat and tidy.

Dan finally pulled up to a two-story farmhouse in the middle of nowhere. The only neighbors were a couple of cows and a wayward chicken. Carolyn eyed them—with their blank stares, even they seemed bored.

She opened the car door and stepped out for the first time on Southern Soil, a clay mud that was a red color she’d never seen before in nature. The mud gripped her feet like quicksand, seemingly trying to suck her down into the bowels of the earth.

“What is this?” she said, gripping the door handle. She tried to get traction, to no avail. Was this how people died in the Amazon? A million thoughts swirled around her brain. She hated that red mud. Before the day was over, it would spread from her shoes to almost everything she owned. She’d spend the next twenty years fighting a losing battle to get it out.

“Welcome home.” Dan wrapped his arms around her, holding her tightly. Was he afraid that she might change her mind? She shifted, trying to get some kind of leverage with the car. He’d let go of her to get their suitcases out of the trunk. It took him a while to notice that she was practically lying across the hood of the car to avoid falling to the ground. Finally, though, the sounds of distress emanating from her throat caught his attention, and he took her hand and led her to drier ground.

She glanced at the bountiful acreage, squinting at it under a furious sun, and then at the house. He seemed to be waiting for her to marvel at it. It was much different from the houses she’d grown up with up north. She took a few steps closer. It had a quaint wraparound porch with a swing, a place where she could imagine having lemonade. Her eyes were drawn upward to some crooked gutters showing signs of wear and tear, the black shutters contrasting with what had been white vinyl siding. A good power wash would do it some good…

Desolate. That was the feeling rising inside her—a house presiding over a large tract of land without any civilization in sight. Where would she shop? Where would she…

“Our neighbors are over there,” he said, pointing past an overgrown field. “The Wallace farm.”

Obviously, “neighbor” meant something different here. In Boston, your neighbor was the one who could pass you a bag of sugar through an open window.

Maybe someday she could talk him into joining a larger congregation in a big city. A place like Nashville maybe. She had to have hope.

Every year on Jesse’s birthday, her parents told her the same scary story about the trains that had collided in Boston when her mother was seven months pregnant with her. They had traveled up to the city to visit Carolyn’s mother. One mistake caused two tracks to line up just right for an accident, and her parents were in one of those trains.

Her father came out without a scratch. Her mother was rushed to Boston Medical Center where she’d lost so much blood they didn’t expect her—or her baby—to survive. Jesse was hanging on by a thread. And her mother’s legs were injured so badly she needed all kinds of x-rays and blood transfusions.

Luckily, Jesse’s older siblings were at their grandmother’s house during this time, so they didn’t have to witness their mother in critical condition.

There was no ultrasound back then, no way to tell if the baby had been injured too. When Jesse was older, she realized it must’ve been hard for them, not knowing if all that radiation would affect her and having to wait those two extra months to find out. When she survived, they called her the Miracle Baby. That was a lot to live up to.

That’s why Jesse decided at age five that she was destined for greatness. Since she’d beaten the odds, she had to do something important in this world to prove that she was worthy and deserving of being here.

After recounting the story, her father said, “But thankfully, you turned out fine.”

“That’s what you think,” Danny teased under his breath. “I think it explains a lot.”

Jesse gave him a shove. “The Lord works in mysterious ways,” she said, taking another piece of cake. “And you’d know that if you weren’t so stupid.”

Danny was a year older than Jesse, with light brown hair like their father’s and a grin a mile wide. The trouble was, he seemed to think everything he said was funny, but to Jesse it wasn’t. She decided that big brothers weren’t funny. All they were good for was making poop jokes and dumb faces behind their parents’ backs when they were talking.

Before the accident happened, Jesse’s older brother and sister had gotten to visit their grandmother, Rose, in Boston a few times. But she died a year after Jesse was born, so she was sad that she’d never known her. Jesse wished she knew what it was like to have a grandmother to eat cookie dough out of the bowl with. Her mother told her that Rose would have said batter will kill you if you eat it raw like that. But Jesse didn’t care. She preferred to imagine her that way. She might have a grandmother on her dad’s side, but he had no idea where she was. So Jesse would imagine what she would be like, round and gray-haired, like a character she’d seen in one of her children’s books, pulling cookies out of the oven with a smile. She didn’t know why, but grandmothers and cookies seemed to go together.

* * *

Jesse spent every morning of first grade throwing up before heading off to school. She knew throwing up wasn’t good for you, but she was good at it, able to projectile vomit all the way from the bathroom door to the toilet. If there had been an Olympic competition for hurling, she could have taken the gold.

This was one of many reasons why living in a small town wasn’t so good. All the teachers knew her parents, some of their kids went to school with her, and nearly all of them went to her church. So everyone knew about her problem. People came up to her parents after services and asked if they should pray for her.

She didn’t like everyone knowing about her problem. But in a small town, everybody knows your business, and they continue to know it until you died…or moved. A lot of people had died before having a chance to get out of Greens Fork.

Jesse didn’t know why she threw up. Nobody did. Some thought she was simply a nervous kid. Her parents worried she might have had something wrong with her intestines, something that might be connected with the accident before she was born. They took her to a Nashville hospital where she had an endoscopy.

“They’re going to take pictures of your stomach with a camera,” her mom told her.

“Why would anyone want to do that?” asked the precocious six-year-old.

“So they can help you feel better,” her mom replied with a forced smile to prove she wasn’t worried.

After the procedure, when they didn’t find anything, the doctor politely told her parents that it was probably all in Jesse’s mind.

When they got home, there was a lot of closed-door, loud whispering. The no-fighting-in-front-of-the-children rule her parents had didn’t mean there wasn’t any fighting. There was such an undercurrent of tension in the Aimes’ household at this time that it was a wonder everyone in the family wasn’t vomiting. No matter how hard they tried the stress would come bubbling up to the surface, usually during mealtimes, giving everyone indigestion.

The stress, Jesse decided when she was older, was created by her father’s need to keep everything under control and her mother’s need to vent. Carolyn was the kind of person who believed it was okay to fly off the handle and spew her feelings from time to time. Such behavior only made Dan uneasy, though, so he’d do whatever he could to “fix” it.

In this case, her dad eventually sat Jesse down and told her that she’d have to learn to calm herself down because she couldn’t live her whole life hunched over a toilet. As it turned out, she didn’t have to. It turned out Jesse was allergic to dairy products. The discovery was made by accident when Carolyn noticed that Jesse, immediately after having her daily glass of milk with breakfast, almost didn’t make it to the bathroom. They took her to their family doctor in Greens Fork, Dr. Jay Henderson, otherwise known as Dr. Jay, who decided to test her for allergies.

All the way home, Dan praised his hometown. “See, those big city doctors couldn’t find anything,” he told Carolyn.

“Uh-huh,” she said. “Don’t miss the turn.”

“Lived here all my life.” His voice had a sharp bite as he turned the wheel. “I’m just sayin’, whenever something big happens, you and everybody else think the only good doctors must be in Nashville. Turns out that wasn’t true, now was it?”

Knowing he’d persist until she admitted that Dr. Jay was a wise sage or something to that effect, she praised him emphatically, doing what it took to make Dan stop talking. She had an instinct for what people wanted or needed, something invaluable for a preacher’s wife. She somehow could always make others feel at ease around her, even if she didn’t always feel the same around them.

Jesse thought her mother was mysterious. Sometimes she was very emotional for no apparent reason, and sometimes she was incredibly calm and cool, like the time Danny ran into a wasp nest. She quietly told Dan to “Call Dr. Jay,” as she tended to his stings. She was a real enigma, a woman with so many layers she put onions to shame. Jesse thought she’d never fully know or understand her.

It was a deceptively beautiful summer day—not the kind of day Jesse would have expected for what seemed to be the worst day of her life. It was a day that began with so much promise, but ended in disaster. It was sunny and bright with the trees and sky illuminated in deep shades of green and blue like crayon colors. Decades later, Jesse could remember everything from that day, especially the sweet smell of honeysuckle lining the gravel road where she walked alongside her best friend.

“Are you scared?” Stephanie asked.

“No,” Jesse lied. Her innocent blue eyes were bright and unsuspecting, and she had platinum blond hair that almost didn’t look real. She was so perfectly gullible, especially where Stephanie Greer was concerned.

Stephanie could make Jesse do anything, and she seemed to know it. With long dark hair and gray, smoky eyes, she was a movie star in Barbie sneakers. Jesse had never seen anyone with gray eyes before. She thought Stephanie was the most fascinating creature who ever walked the earth. She would follow her anywhere—even to the river’s edge.

“There’s water there, but we ain’t goin’ in it.” Even Stephanie’s reassuring voice couldn’t drown out the warnings of Jesse’s mother, who had made it clear that nothing but death by drowning awaited them at the river. Jesse had had to promise a million times she wouldn’t go there unsupervised.

Something about being with Stephanie made it all right. She seemed an old soul with all this wisdom packed into her six years. Whatever it was, Jesse suddenly didn’t care about the warnings. Stephanie was worth the risk.

The girls walked under the sun, their shadows stretching and merging across the quiet road toward the river. Leaves rustled as they got closer. They could hear the spray of a waterfall deep inside the forest. It was like stepping into a fairy tale, with rays of sun beaming down through centuries-old trees. In a single moment, Jesse believed God was there. She’d never felt that before, especially not in church. Everyone in church was too busy sticking their noses into everyone else’s business to pay attention to God, whispering about who was sitting with whom or whose outfit didn’t match. As for Jesse, she couldn’t pay attention because the lacy dresses her mom made her wear were always too itchy or scratchy.

Here, though, as a gentle wind blew through the trees, she could almost feel spirits from the past and present encircling her and her friend, as if they knew them. It was a strange feeling that lasted only seconds, but it felt real.

When the trees parted, the path led them to where clear water rushed over the tops of protruding rocks and sparkled like liquid diamonds in the sun.

“See? Nobody’s drownin’.” Stephanie flashed a grin.

For at least an hour, they sat on a large flat rock at the river’s edge. Jesse could smell the fresh earth under her shoes. Something about this day was so special, she wanted to hold on to it somehow. She reached beside the rock and picked a bunch of the green, leafy plants growing there and presented them to Stephanie like a bouquet.

“Silly,” Stephanie said dismissively. “Girls don’t give other girls flowers.”

Jesse’s face turned red, and she quickly dropped the bouquet. She felt embarrassed, although she wasn’t sure why.

“Come on.” Stephanie proceeded to show her how to find a properly sized walking stick to navigate the rocky trail that ran beside the river.

As Jesse followed, she kept wondering what she’d done wrong.

Stephanie’s footsteps in the dirt led them farther into the forest.

“I’m not supposed to go this far,” Jesse said anxiously, knowing she shouldn’t have been there at all.

“The trick is to find a stick that’s the right size. You don’t wanna get one too big or too little.” Stephanie handed her a stick that was about her size and kept on going.

“Why do I need a stick?” Jesse asked.

“It’s for hikin’.”

“We’re hikin’?”

Stephanie stopped and watched her friend stepping gingerly over uneven, rocky ground. “Not if you go that slow,” she said.

Jesse threw down her stick. “I’ll go as slow as I want! You’re not the boss of me!”

“Okay, I’m sorry,” Stephanie said, resuming the pace. “Geez.”

As they walked, Jesse picked up some brown stones she’d never seen anywhere but there. They were smooth and perfectly round. She turned them over in her hand and chose to keep one as a souvenir of this day. It was about the size of an egg with a reddish tint that looked like clay. That would be her treasured rock. At age six, everything was of monumental importance. For her, this rock would signify everything magical she had felt in the forest that day.

Eventually they came to a place where the water seemed to stand still, expanding like a lake, surrounded by green and sounds of buzzing here and there.

They stopped walking when they saw their reflections in the standing water.

“You’re pretty,” Stephanie said suddenly. Jesse said nothing. While Stephanie seemed to have no problem stating what was what, Jesse was used to keeping most of her thoughts to herself. The sun swept across the water, making light dance all around them.

“Stephanie! Time for supper!” Arlene Greer’s voice echoed throughout the forest. Her tone was so loud and sharp that Jesse was sure she must have spooked all the animals.

The two girls darted down the trail, then began crossing the undefined rock pathway to get to the other side of the river. Stephanie had already made it, while Jesse was on a rock in the middle of the river, trying to keep her balance. As she stepped off it, some slime on it made her foot slip. She started to go down, but right before she hit the water, Stephanie caught her, hanging on to her arms, helping her regain her balance.

“I’m gonna die,” Jesse kept saying, feeling certain that this was the punishment for disobeying her mother.

“No, you’re not. You know how to swim, don’t you?”

“Yeah.”

“The water’s not even that deep!” Stephanie laughed, then led her back over to the other side.

“I swear, you’re gonna kill me,” Jesse said when she successfully reached the riverbank. She wiped sweaty hands off on her shorts and caught her breath. As they continued making their way through the forest, there was a loud rustling close behind them. Jesse grabbed Stephanie’s arm. “What was that?”

“Could be a bear.” Stephanie couldn’t hide her smile; she liked to tease her.

Jesse shoved her playfully, but she hadn’t let go of her fear. “Don’t say that to me. You know how I get.” She’d told her friend about the stuffed black bear keychain she’d gotten in a gift shop during a family trip to the Smoky Mountains—never mind that she had no keys. Since discovering that black bears roamed around east Tennessee, she’d been worried about whether or not they’d show up in middle Tennessee.

“I can’t guarantee, Jess. This is North America.” Stephanie sounded like an authority on everything, even when she was kidding.

“You said it was safe!”

“It is,” the wise-looking brunette said with great confidence. “The only bears in Tennessee are those black ones that don’t hurt nobody.”

“What about the ones that can hurt you?” Jesse asked. “Are you supposed to play dead or run? I saw it on a nature show, but I can’t remember which bears you do what with.”

“I don’t know,” Stephanie admitted. “I’d probably run no matter what.”

“Yeah.” That seemed the most sensible thing.

They continued down the road, wiping any traces of mud off their shirts and scraping their shoes against the gravel to hide all evidence of their secret adventure.

Carolyn Aimes waved tiredly at Arlene through the car window when she came to pick up her daughter. She and Arlene always exchanged the tired smiles of two mothers who understood each other. They seemed to Jesse like friends, but Carolyn rarely got out of the car.

When the girls reached the front yard, Ms. Greer gave Jesse a big hug. “You come back any time, y’hear?” Ms. Greer resembled an older Stephanie, the same gray eyes, even the same dimples in her cheeks.

“Thanks.” Jesse turned to Stephanie and gave her a hug. It was nice having a secret just between the two of them.

“You’re welcome.” Stephanie winked at her. It seemed that she was always making Jesse do things that scared her. And almost every time, it turned out to be okay. No one drowned in the river that day.

A Helen Reddy song was playing faintly on the AM station as Jesse climbed into the car. “That ain’t no way to treat a lady, no way to treat your baby…”

“Did you have a good time?” her mother asked, pulling out of the driveway.

“Uh-huh.”

“Put on your seat belt.”

Jesse did as she was told, taking one more backward glance at the trees hiding the enchanted river. She felt sure their secret would be safe.

“We have to get groceries,” her mother said.

Jesse was thinking about her adventure with Stephanie, paying little attention to the mundaneness of ordinary life. She’d slipped into an other-worldly existence, one that nothing could pull her out of…not until The Great Grocery Store Meltdown, as it would come to be known.

Carolyn liked to buy seafood because it reminded her of home. She grew up on the North Shore of Boston in an old Victorian house on a street that was lined with old Victorian houses. Her family was used to eating lobster two or three times a week. They even fed it to their cat, who was named Hank. They later found out she was female, but the name stuck anyway. Hank would sell her furry little soul for a piece of lobster meat.

One time they kept putting out bowls of lobster right after the cat reached the bottom of the back staircase. Once she caught a whiff of more lobster, she’d climb the stairs again and clean out the bowl. Hank finally got so full she lay on her back with all four paws up in the air. They thought she was dead. To see exactly how gluttonous she was, Carolyn’s mother put out another bowl with the last few chunks of lobster and one more time set it outside the back door. Amazingly, that cat found a way to roll herself upright again, dragging herself up each step as if it were her last. But she made it. If there was lobster, Hank would eat it, even if it killed her.

In Greens Fork, Carolyn had no choice but to shop at Rooster’s Food Emporium, the only grocery store in town. It was right next to the Stop ’n Slurp, a place you went to get snacks or sodas when you were in a hurry. Kids mostly went there.

The décor inside Rooster’s Food Emporium hadn’t been updated since the 1950s. The walls were a sickly pale green, which clashed terribly with the faded red, now pink, rooster painted on the back wall. It was as though the owners had given up years ago.

Carolyn went there to order live lobsters, though they only kept a small few in the tank since most of the locals didn’t know—or want to know—what they were. Carolyn pointed at the tank like a woman on a mission.

“You want to get the liveliest ones,” she explained to her daughter. “They taste the best.”

Jesse preferred to picture her lobster as something red on a plate, not green and black, and certainly not moving.

When Carolyn indicated which ones she wanted, they were always packaged inside a cardboard box. The box wasn’t big enough, so their antennae poked out at the corners, each one moving. To the untrained eye it probably looked as though she was carrying around a giant insect. As Jesse made her way down the aisles with her, she saw the women who were there pointing at the cardboard box and whispering to each other with the same sense of urgency as if Jesse’s mother was rumored to be a serial killer. It was the first time she’d really noticed it, but it seemed her mother must have gone through this every time she bought lobsters.

Everyone has a breaking point. Even Carolyn, who, at first glance, seemed as proper and refined as mothers on old TV shows. On this particular day, though, she’d had enough. The whole town was about to see June Cleaver blow.

They reached the cashier, who was a girl of about seventeen. She dragged the items over the scanner, popped her gum and clicked her long fingernails until she got to the box with the waving antennae. She stopped, giving Carolyn a face of disgust.

“You gonna eat that?” she asked with a sneer.

Carolyn, the woman with more layers than an onion, didn’t appear to have anger issues. In fact, no one had ever seen her have a temper tantrum, which made the next few moments all the more shocking and memorable to Jesse. And everyone else within hearing distance. The outburst her comment provoked might have rated a raised eyebrow or two in Boston, but in Greens Fork it was tantamount to the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius.

“Yes!” her mother exclaimed in a tone that made the other cashiers stop what they were doing. Carolyn leaned over the counter, her eyes fierce and her hair on fire: “I’m going to take them home, throw them head first into boiling watah, and I’m going to eat them!” She chomped her teeth together, making a snapping sound that sent a cold chill throughout the store, one that didn’t come from the frozen section. They stormed out of the store so fast Jesse didn’t even remember how they got to the car.

It was a long, quiet ride home. Every now and then Jesse snuck a glance at her mother to see if she was okay. All she saw was an expressionless face, a mouth that was a tight, thin line. Dropping her gaze, she studied the big dents in the thighs that poked out of her mother’s skirt. Jesse had never seen her mother in a wheelchair, of course, and then on crutches, but she’d seen photographs of how she looked after the accident. She walked fine now, had for as long as Jesse could remember. But she’d never known her without those big gashes in her thighs. On one of her legs there was even a line of stitches. Her mother was always pulling her hemline down as far as she could to try and conceal it, but people stared anyway.

Jesse wondered why her mother always wore skirts and dresses, especially when she didn’t want people staring at her legs. It made no sense. A lot of grown-up things didn’t make sense. Like when the members of the congregation kept staring at Jesse before they knew about the food allergy, waiting to see if she was going to toss her cookies in church. Why were her intestines more important to them than God’s message? Why did anyone care about her mom’s scars or what they ate for dinner?

Jesse glanced out the window, took a deep breath and reached over to pat her mother’s leg.

* * *

Carolyn stared at the horizon, willing the tears to stay inside her eyes as she drove. If she cried now, it would be the second time this week, and she didn’t want to alarm the kids.

What had begun as a sabbatical, at least in Carolyn’s mind, had, she realized, turned into a permanent living situation. When her mother was alive, hearing her voice on the phone gave Carolyn hope that she might someday return to her hometown. Not that she could picture Dan as a reverend in Boston. But that was a minor detail. Now that her mother was gone, her ties to Boston had grown more distant—friends were always too busy picking up kids from school to talk much to her on the phone—and her hopes of someday leaving this town were tied to wisps of conversations about other places. She’d mention something interesting about a place she’d read about and Dan would seem keen on the idea of visiting it. Then he’d add, “Next time we go on vacation.”

It was a survival skill, maintaining this perception of impermanence. Not allowing herself to memorize the brands of gum they carried at the Stop ’n’ Slurp mini-mart, for instance, because she was sure she wouldn’t need to know in the long run. Which meant even now, after one pack of gum had turned into hundreds, as she waited in line she always had to check what brands were available.

She turned toward the road to home. Dan was no longer the most handsome man she’d ever seen, but what she’d felt in the beginning had been replaced by what she hoped was something deeper. She told herself she loved him in spite of his imperfections. She wouldn’t—couldn’t—dig any deeper than that, wary of uncovering something she couldn’t handle. If the foundation of their marriage wasn’t as solid as she assured herself it was, what was all of this for?

* * *

That night Jesse cracked into her lobster with reckless abandon. She savored the taste of the sweet meat dipped in melted butter. She didn’t want to see how it got on her plate, though.

Her sister Ivy, who was two years older than she, was a dainty eater. She always struggled to crack the claws. The nutcracker would slip out of her hand, and she’d huff in frustration. Her big sister had so little strength, it seemed the heaviest thing she could hold was a hairbrush. Jesse teased her all the time because when they would wrestle around on the floor, Jesse could always pin her down. For this reason, Ivy said that sometimes she felt like she had two brothers.

Danny was as messy as Jesse, but more obnoxious. He liked to scoop out the green stuff and plop it on everyone’s plates to see their reaction. A meal never went by when their mother didn’t have to say, “Danny, cut it out.” Or “Do that again and you’ll go to your room.” Danny was the reason why parents said things like that.

Their father didn’t eat lobsters because they had eyes. He had a strict policy not to eat anything if he saw its eyes. So on lobster nights he’d stick to his pork and beans out of a can. He never minded that cows and pigs had eyes, only when the eyes were still on the food they were eating. Interestingly, he had to have a side of canned pork and beans with every dinner, no matter what it was.

“You should see how they look at me, Dan!” Carolyn exploded, taking her anger out on the lobster in front of her.

“You sure you’re not overreacting?” he replied. He always said she was overreacting. He dangled the word like a match over gasoline. Tonight was an especially bad night to say it.

Jesse cringed, waiting for part two of the Grocery Store Meltdown.

Carolyn twisted in frustration, though she didn’t leave her chair. Her husband was a Southern Soil through and through, content with his pork and beans, the sun rising and setting the way it was supposed to and the idea that it was best not to ripple the waters. Getting along with everyone was the name of the game. He’d never really understand what a struggle it had been for her to live here.

“Now I’m the evil lobster lady of Greens Fork!” Her face was red. “They look at me like I’m an alien!”

He patted her shoulder. “Well, you’re the prettiest alien I’ve ever seen.” He gave her the patronizing smile that said, “I just want your problem to go away.”

She kept on eating, chewing louder as if that would make him understand.

“Heavens! We forgot to say grace.” Dan was more concerned about everyone’s souls and the prospect of hell. That was far worse than the possibility of his wife being on the verge of a nervous breakdown.

The Aimes’ family joined hands and bowed heads. Jesse took Ivy’s hand, which was covered in sticky lobster juice.

“Eeww!” Jesse exclaimed, pulling her hand away.

“Enough,” Carolyn commanded, her eyes burning through Jesse.

After the display in the grocery store, Jesse thought it wise to listen to her and immediately took Ivy’s sticky hand again.

“Dear Lord,” Dan began as he did from the pulpit, “let us be truly thankful for what we’re about to…for what we’re eating at your table. Amen.”

The family ate in a dining area inside the kitchen, cramped together at a square table, surrounded by flowery kitchen wallpaper that evoked a feeling of forced cheerfulness. Though the table in the dining room was much longer, it was reserved for guests, so none of the kids ever got to sit there. Carolyn and Dan hardly used it, either. Another strange thing about grown-ups…keeping rooms in the house that they didn’t use.

Jesse almost made it through dinner without revealing the big sin she’d committed earlier in the day, but her skin betrayed her. It started with her hands, then spread up to her neck. Before she knew it, she was itching like crazy all over, her fair skin covered in big pink blotches.

“What’s the matter?” Carolyn asked when she noticed Jesse scratching.

“Nothin’. It’s nothin’.” She’d hidden all known evidence, but something was happening that she had no control over. It scared her.

Carolyn took Jesse to the upstairs bathroom where the light shone a spotlight on the pink patches. “You’ve got poison ivy!” she hollered. Her voice was hoarse from all the yelling she’d already done that day.

The green bouquet Jesse had tried to give Stephanie—that must have been poison ivy.

“Am I gonna die?” Jesse’s blue eyes filled with worry. Considering the intensity of her mother’s reaction, it seemed as though she wasn’t long for this world.

“No.” Carolyn took calamine lotion out of the cabinet and began rubbing it all over the young girl. “Where were you today?” she demanded.

Jesse couldn’t lie to her. All she could think of was fire and brimstone and going straight to hell if she told a lie. “The river,” she mumbled. She hung her head like a prisoner awaiting execution.

“The river?” Carolyn screeched. “I told you not to go there! Was Arlene with you?”

Jesse cocked her head, not understanding the question.

“Stephanie’s mother?” Carolyn said. “Was she with you?”

Jesse shook her head “no” and sealed her fate.

“I don’t believe it! You used to obey me.” Then her mother began muttering incoherently, as she stormed into Jesse’s room and yanked pajamas out of the drawer. She seemed to be talking to herself and to Jesse at the same time. “Everyone in this town…sees me as some kind of aberration…Now my first grader is already defying me! God knows what’ll happen when you’re a teenager!”

Jesse was sent to bed early that night. As her mother closed Jesse’s bedroom door, her words pierced through the walls: “I don’t want you seeing that Stephanie Greer again. She’s a bad influence.”

With that, the darkness of Jesse’s room spread across her face, hiding the hot tears that leaked down her cheeks all night long.

It was a lonely summer for Jesse, because without her mother’s permission she couldn’t go to Stephanie’s house. Luckily, her sister Ivy played with her, although she had very specific ideas of what playtime meant. She’d water the weeds their father had asked them to pull. Then she’d plop wet mud on them and say, “With this super fertilizer, your yard will be the talk of the neighborhood.”

“Who are you talkin’ to?” Jesse asked.

“The studio audience,” Ivy replied, rolling her eyes. “Duh.”

“You’re crazy.”

“You don’t have an imagination.” Ivy patted the caked mud to get it to look just right. She’d tell Jesse to grab the plastic pitcher and help her, though Jesse didn’t see what the point was.

“They’re nothin’ but weeds,” Jesse said.

“What if they’re small trees that will grow up to be majestic…”

“They’re weeds!”

“Ugh! You’re not fun!” Ivy argued.

“Well, guess what? Your fertilizer show ain’t fun, either.” Jesse got up and dusted herself off.

She wouldn’t stay mad for long, because she could always find something to do. Summer days in Tennessee were something out of a movie—hazy days, green, sweet-smelling grass, and at sunset, the sun looked like a giant plum lowering in the sky, so close you’d think you could take a bite. How Jesse wished she could share these days with Stephanie.

Jesse liked to climb trees on their property. Her favorite was one with a trunk that split and went in many directions. She’d pretend it was a monster she had to battle and crawl up one of his arms to get to the source of his power. Somewhere at the top of the tree was his head. Sometimes she’d climb to a certain branch and look out at the valley and pretend there were other houses there. “There’s the Kelmans’ place,” she explained to Ivy. “They have one boy, and he doesn’t like to go outside because he has this disease that keeps him indoors.”

“What’s the matter with you?” Ivy’s brow was crinkled.

“I’m having an imagination,” Jesse explained.

“You’re making up people who don’t exist,” she said. “That’s insanity.”

“And playin’ ‘Fertilizer’ is normal?”

They always argued but usually found something they could agree on—like trapping frogs in jars, staring at them a while, then setting them free. Ivy was fascinated with wildlife. She could tell the difference between a robin and a warbler. She wanted to share her knowledge with her sister, but Jesse had the attention span of a fruit fly.

“Some birds carry diseases,” Ivy told her.

“I don’t wanna know,” Jesse said. “It’s bad enough I gotta worry about bugs and poisonous plants. Now birds’ll kill me too?”

“Why does this upset you?” Ivy seemed truly concerned.

“’Cause of the tick thing,” Jesse said.

That was their brother Danny’s fault. Jesse was the kind of child who was better kept in the dark about blood-sucking insects. But Danny couldn’t resist not only telling her about them, but also pretending that there was one stuck on her head.

Jesse didn’t like playing with her brother very much because he liked to do a lot of mean things like that. He’d climb trees too, but only so he could see how far down he could spit. There wasn’t much fun in that.

Living so far away from town, each of the Aimes kids would make up things to do to keep themselves occupied. Especially Jesse. Her mind became her playground. She learned to use it more than her bike. Or board games. But on rainy days, Monopoly and Sorry! would be dusted off and rediscovered.

Their closest neighbor was still the Wallace farm. They were the most tired-looking family Jesse had ever seen. They got up at three in the morning. They were always tending their crops and working the fields. No one ever saw any of them without a bucket in their hand. Dan said he thought the Wallaces had kids only to have extra help on the farm. But even they were a good distance from the Aimes house, so Jesse and her siblings didn’t play with them very much.

Jesse began to count down the days until summer was over. She couldn’t wait to go back to school to see her friend Stephanie again. Her mother couldn’t separate them at school.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.