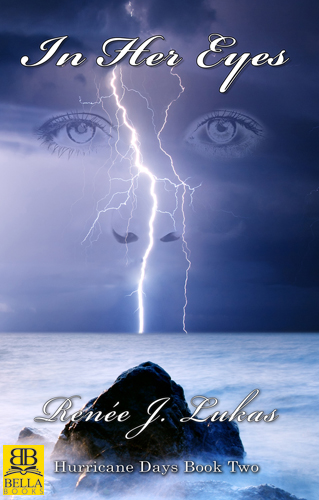

by Renee J. Lukas

Rolling Stone is about to get the scoop of a lifetime. Rock star icon Adrienne Austen finally wants to tell her story, including what happened between her and former Governor Robin Sanders. Rumors of an affair with Adrienne sent Robin into hiding, but the publicity did nothing to diminish Adrienne’s continued rise to fame with her band, Eye of the Storm.

Was Adrienne truly the bad girl that everyone believed her to be? Was she really involved in Robin’s disappearance? Find out the answers in this revealing sequel to the best-selling Hurricane Days.

You must be logged in to post a review.

Cory

My name is Cory Watson. I’ve been a reporter for Rolling Stone magazine a couple of years now. I write decent pieces, but nothing to get me noticed by anyone so far. So I flipped out when they gave me this assignment. I’d interviewed record execs, but since I was still new by their standards, I’d never interviewed a real star yet. And this wasn’t a star—she was an icon.

At sixty-five, Adrienne Austen was still touring with most of the original members of her band. She had jagged blond hair and could rock a pair of leather pants like you wouldn’t believe. She was my grandma’s age, but my grandma couldn’t wear pants like those. I don’t even want to picture that.

I was going to meet her at her apartment in Greenwich Village that afternoon. She’d been living in New York for the past ten years or so. She’d said it provided better access to the entertainment world and, at the same time, was a better city to be anonymous in, something she craved after all of the scandals surrounding her. She did admit to missing Boston, though, the place where she and her band had become underground rock sensations.

I was a nervous wreck, because, c’mon, she was an icon. I went over my interview questions again, repeating them in my head, refining them until they sounded natural.

In the elevator, I kept clearing my throat. All of a sudden I had rocks in my esophagus, threatening to make me sound like a pre-pubescent teen. I pulled at my already loosened tie, needing some air. The truth was, Adrienne Austen was my idol. I had every CD she ever put out. I didn’t want to just download the songs, like my friends did; I wanted the album art and CD covers too. I was one of those quirky guys who collected CDs and even vinyl if I could still find it. I loved haunting music, the darker the better. All the notes of longing, of unrequited love—I suppose I related to that since that described my entire adolescence. Adrienne’s voice—and her band, Eye of the Storm—were the voice of my teen years. I’d lock myself in my room and play Eye of the Storm for hours on end, scaring my parents. Add to that the fact that it was widely known how she preferred women, which only added to the intrigue. It would’ve been so much easier had they given me someone else to interview, like the folk-rock guy, Ed Fudge, or the rapper Ping Pong. But my first celebrity interview would be with the woman I’d adored since I was thirteen. At this point, she’d become a legend in my mind, and I was a little afraid to meet a mortal woman who could disappoint me or change the image I had of her.

With each floor the elevator passed, I took a deep breath. I had to keep it together and not act like a star-struck schoolboy. I knew Ms. Austen didn’t look the way she did in her twenties or thirties, but unlike some female singers who get a lot of unfair shit for growing older and their looks changing, somehow nobody cared about this with Adrienne Austen. I’d be out with my guy friends, and if the subject came up, they’d be like, “She’s a real badass.” I guess it was that she had the same attitude she always had, and that’s what mattered most. I wouldn’t tell my friends, but I found the extra lines on her face sexy; I even thought being older made her sexier, the way I think we all get sexier with our experiences. But I’d never tell my guy friends that. They’d laugh at me.

When the door slid open, I followed the directions on my now-sweaty Apple watch. Reporters like me took pride in holding on to vintage artifacts like those, but the truth was, I was too lazy to take it off. The watch told me to take a right out of the elevator. It was less than a minute before I was there—face-to-face with Adrienne Austen’s door. I thought I’d crap myself.

The door opened, but I didn’t recognize the woman.

“Elaine Ford,” the woman said with a tired smile, shaking my hand. “You’re here for the interview?”

“Yeah, yes,” I responded. “Cory Watson, Rolling Stone.”

“Come in.” She gestured to a long hallway. It opened into a wide living room with an impressive view of the city. I imagined it was really romantic at night, all lit up. “Would you like something? Coffee?”

I glanced around, remembering that she was still talking to me. “Uh, no. I’m good.”

“I’m her assistant,” Elaine said. “Let me know if you need anything.” She was polite, but seemed as though she was already late for something.

“Thanks.”

“She’ll be out in a minute.” Elaine exited down another narrow hall, leaving me to my anxiety.

I tried to get comfortable in the stuffed chair near the sliding glass door. I kept staring at the view of a quaint balcony, and all the electric cars filling the street below—all clones of each other, and getting smaller every year. Somehow, the colors lime green and white had become the favorites. Looking out, all I could see was a sea of lime green and white. I stuffed my iPhone 2036 into my pocket and sort of hoped that the chaos below would lull me into a meditative state. It was impossible, though. I’d never been so amped to talk to someone.

The apartment was turn-of-the-millennium décor, which had come back in style, with old-fashioned wood floors, a ridiculously high ceiling and open kitchen looking out into the living room. There was a loft right over my head with a glass floor; I imagined the bedrooms were up there. The place was inviting, with a hint of cigarette smell. Flushed with anticipation, I waited for what seemed like eternity. Just as my shoulders had begun to relax a little…

A throaty and familiar voice cut the air.

“You smoke?” It was her.

“Uh, no.” I jumped up immediately and extended my hand. “Cory Watson…” It was a strange question. Hardly anyone smoked anymore; that vice seemed to be reserved for rock stars and a few actors.

“Rolling Stone.” She lit up a cigarette, not taking my hand. Her almond-brown eyes crinkled in that same smile, the one I’d seen many times before on the downloaded videos that had played on my bedroom wall when I was growing up. Her hair was darker, a caramel color streaked with blond highlights, and a little shorter, just above her shoulders. She brushed some jagged bangs to one side and looked curiously at me.

Or maybe it wasn’t curiosity at all. Suddenly I realized—she’d met a million me’s in her lifetime, and I was not as exciting to her as she was to me.

* * *

We sat at the little table on the outside balcony. Autumn was kicking up some cool breezes out here. I kept trying to smooth my hair so I wouldn’t look like a complete slob. Suddenly none of my rehearsed interview questions seemed good enough. Dammit, Cory. Remember why you’re here.

“Your tour,” I blurted. “Some are speculating that this will be your last tour. Is that true?”

She took a drag off her cigarette, sat back and appraised me. She was probably wondering how I’d gotten as far as I had. “My last tour will be the one right before I die. Is that really what you want to talk about?”

My mouth went dry. The wind caught the silver silk shirt she wore, and the collar flapped up on one side. It was a freeze-frame moment, reminding me I only had one chance to get it right.

Obviously, she was a person who could see through bullshit. My best bet here was honesty. She might even like me for it, since hardly anybody tried it anymore. She knew what my real question was, but it was rumored that she never wanted to talk about it. So I struggled.

Why would she tell me, a nobody, when she wouldn’t tell anyone else? I reminded myself that she hadn’t granted interviews in a long time, and by agreeing to this one, she might be willing to talk about…it.

“I’m sorry,” I said plainly. “I know I don’t have a reputation yet.”

Was I really apologizing for myself? Apparently so.

“I didn’t have a reputation either,” she said, “until guys like you noticed me.”

Oddly, her remark put me at ease, as if she understood the struggle of a guy trying to make a name for himself at a top magazine, one of the rare few still in print. Of course she understood the struggle. She’d lived it.

I smiled a little, thinking about what I really wanted to know, what everyone wanted to know. It would be a more interesting angle than a piece about whether or not this tour was her last. But my editor assumed that would be all I could get. She wouldn’t believe it if I could land a bigger story.

“Okay,” I chuckled, double-checking that the “record” option was set on my watch. I braced myself and dove off the cliff… “Did you kill her?”

My voice was surprisingly soft, but the question was indelicate, to say the least. Of course I was referring to the famous politician, Robin Sanders, former governor of Georgia, who went missing after a rumored lesbian affair with Adrienne Austen. Before Adrienne could respond or kick me out, I added, “I don’t believe it, you know. But it’s one of those mysteries that still kind of hangs on.” As if she didn’t know.

“Is that what people think?” she asked with apparent surprise.

“It’s about half and half.” I’d assumed she knew.

She crushed the remainder of her cigarette in the ashtray and gazed out at the murky skyline, expressionless. “Whatever sells.”

“So you didn’t?”

She turned to me, a slight smile escaping her lips. She leaned closer, as if she was going to spill a big secret. She looked at my recording watch. “Turn it on. I’ll give you the real story.”

Adrienne

I used to be cautious with reporters, only telling them what I wanted them to know. But something about getting older…maybe I wanted to reveal more, wanted, needed, to be understood more. Whatever the reason, I didn’t tell Cory Watson everything, but I ended up telling him way more than I’d intended to.

I came from a small town in central Florida. No beaches, but miles of orange groves and bright, electric sky you’d swear was so close you could touch it. I never talk much about my hometown because it was uninspiring. A flat, dead place. When people talk about where they come from, it always seems like the place they grew up is a part of them, something they carry with them. Not me. Miles of monotonous orange groves never became part of me. And the sense of hopelessness, sameness—people getting up, going to work and drinking themselves into the daylight—nobody lived there, only existed. You didn’t belong there if you had plans or, even worse, dreams. And as it happened, my dreams were just too big for that place.

My favorite memories were of lying in the grass in front of my house and watching clouds drift by like puffs of smoke. Those are the good memories. Whenever my dad yelled “Adrienne!” because I hadn’t cleaned my room good enough or he was blind drunk…those aren’t so good.

My mom skipped out when I was about six or seven. I don’t remember her much except for the two grueling years of piano lessons she forced me to take. After the first lesson, it was obvious I wasn’t going to be the next Chopin, but Mom had delusions of bringing high culture into our white trash family. At least that’s what it seemed like when I remembered her. She said things about me making something out of myself, and because I could play music by ear, she assumed I had a gift for music. Honestly, I could pick out a tune after hearing it, but I didn’t care much for the piano.

After Mom left, Dad said I look just like her. I always thought that’s why he hated my guts. I reminded him of a tragedy, everything he thought went wrong with his life. That’s probably why he preferred to look at me only through the prism of amber light from his bottle of Jack Daniels.

In high school I was that girl who loved the attention I could get from guys. If you were a boy, I was your worst nightmare, a black widow, trying to get you to fall in love with me, doing whatever it took, especially if you were a “challenge.” Then once I had you, I was done, on to the next one. I’m not proud of it now, but back then I was.

I had this friend, Gwen Tolbert, senior year. I didn’t like “like” her; she was just a fun friend who could get into more trouble than I did, which impressed me.

On the side of my house was an old treehouse left there by the last owner. Since Gwen lived only one street away, she used to come over and we’d hang out and smoke up in the treehouse. My dad was hardly ever home, so I usually got away with it. One Saturday afternoon, she told me to meet her up there, said she had something she wanted to show me. I remember it was a really hot day. I was wearing jean shorts, but the sun, the thick air, stuck to my neck and arms. I felt drops of sweat sliding against my inner thighs as I climbed the ladder.

The treehouse was basically a one-room enclosure with walls and one window. We lay on a worn-out rug covering the wood floor, facing the doorway so we could see if anyone was coming up. There was no door. It sucked when it rained, because rain blew right in. I’m surprised the thing stayed up; I think the wood was rotting. What I remember most is that the rug smelled really bad.

Anyway, we lay on the rug and Gwen showed me a couple of issues of Playgirl magazine.

“Where the hell did you get this?” I asked.

“I subscribe,” she said with a proud swagger.

“Your parents know?” This was back in the days when, if you ordered something, it came to your mailbox, and, depending on who got the mail, you could be grounded for weeks.

“I have a post office box, silly,” she said.

“In town?”

She nodded, a little annoyed that I wasn’t more focused on the centerfolds. But the means by which she could do something so naughty fascinated me. It automatically gave her an air of coolness.

“Anyone can get one,” she explained. “You just pay a fee.” She was ahead of her time, talking like a mature woman with teased-out, blond hair and multiple ear piercings. She was a true rebel, not a pretend one. I learned from Gwen Tolbert that the difference between being a real rebel and a wannabe was believing it. If you owned the role, you were the role.

I flipped through the pages. I knew about all the men’s magazines. I’d seen my dad’s Hustler and Penthouse that he kept in a box in the closet that he thought was a secret. I’d seen all the women posing, spread-eagled on a bed or in a clump of hay in a barn. Weird. Sometimes they were on their knees or doggy style. Not these guys. Each issue I glanced through, the guys were positioned like Greek gods, standing upright and proud even, with everything hanging out below the waist. One guy was standing on a beach, another in some other outdoor place. But nobody was doggy style. Not a single one. It didn’t occur to me to be pissed off about the different representations, not until I met my college roommate a year later. She was pissed off at everything, and she wouldn’t be satisfied until I was pissed off too. But more on that later.

“Look at this one,” Gwen cooed and moaned. It was a spread of their “man of the month,” dressed as a chauffeur, who had part of his uniform missing. “Umm.”

As she laughed, I remember staring at the fake chauffeur, then saying, “He should get his money back. They only gave him half a uniform.”

She didn’t find my joke as funny as I did.

“Okay,” she said. “Which one would you do it with?”

A challenge was posed. I had to flip through both magazines to pick the “just right” one. The truth was, it didn’t matter. They all looked alike to me. They blended together into one long, naked, flesh-colored penis. Then I landed on a picture of a black guy with one of the largest I’d seen. He stood out, not only for that reason, but because he was the most obviously different from the pack. Even the hairstyles were the same—short brown hair, some a shade lighter, some darker. But this black guy, I could remember him. So I picked him.

“Tony?” she squealed. “You like the big ones, don’t you?”

“I don’t care about size,” I replied. “Not really.”

“Sure you don’t.”

The only way to answer was with a smile. I tucked my legs up to my chest and watched a palm tree starting to bend. The treehouse creaked as the wind picked up. A white sky turned gray in the doorway. I knew a storm was coming. But the real tumult was brewing inside of me.

That was the closest I have to a memory of when I felt like I was different. Some people can pinpoint the day and time. For me, it was kind of a gradual learning. But that day with Gwen, I could not only see, but feel, the differences between us, stretched out like an expanse of ocean. Her genuine fascination with the opposite sex was something I couldn’t conjure in myself. It was a scary, sinking feeling. I tried to ignore it as I watched the sky get so dark it almost looked like nighttime within seconds. At the first rumble of thunder, I started down the ladder.

“C’mon, let’s wait it out in here,” Gwen said.

“I don’t think so.” I was sure the treehouse only had a few more months to survive.

“C’mon! Live on the edge.”

“Oh, I am. More than you know.” I grinned at her as though I was completely in control and not at all scared that my treehouse was going to come crashing down.

Adrienne

My dad, Jack Austen, was a big guy—tall and with enough muscles to be a human Popeye. His actual job was working at the only plant in town. They manufactured saddles, ropes and other shit for the rodeo down in Arcadia. That was a big deal here.

I had one thing in common with my dad—I liked women. He liked ’em so much, Mom left him. Of course, it took me forever to admit to myself that I was gay. In the meantime, I just said I was in a prolonged experimental phase, wondering if I could be faithful to anyone, bound to the same person forever. When I met Robin, my soon-to-be college roommate, I was too scared to handle it. But I used to think it would be cool to share the roller coaster together, to watch someone grow and change as you go through life side by side. I’d imagine sitting on a porch, deciding what movie to go see on the weekends. Of course, I wasn’t around to see the changes in Robin, and years later I was confronted with a monster. But I’ll get to that.

One night I heard Dad thrashing around in the house while I was up in the treehouse. I knew he was drunk. He called for me, but I wouldn’t come down. Why go through that again? I hid out for a while until Jerry Jones, my friend from school, came over. He’d told me he saw the flicker from a candle I lit up there and knew right away where I was.

“Your dad didn’t invite you in?” he joked. “To share a beer?”

“Whiskey,” I corrected. “That’s his drink of choice.” I left out the part about how I got yelled at with beer and slapped around with whiskey. I remembered as a child that feeling—rippling waves of fear—the moment I saw him empty the last can of a six-pack and pull out the Jack Daniels. That golden brown liquid was poison and represented everything bad about my childhood. “He works his way up to it, but yeah, that’s his favorite.”

“Huh.” Jerry flipped his shaggy blond hair out of his eyes. He had one of those eighties hairstyles—not as bad as Flock of Seagulls but one of the lopsided styles where he had to keep flipping most of it to one side. In a few months, he’d add a beard, a shade darker than his hair, to his already scruffy face. “My mom can down a six-pack in less than an hour.”

“Wow.”

We compared notes on our alcoholic parents. At the time, I thought it was kind of funny. But in retrospect, it was sad. With Jerry, though, I wasn’t sad. He was a bad boy whose belly was paunchy from too many chips and dip, and he wore ten-year-old T-shirts that threatened to expose that belly. He had a round baby face and the kindest, happiest smile you ever saw. He worshipped the women of the band Heart and his favorite pastime was laughing at dirty jokes. We got along great.

I remember that Jerry was a little awkward around girls. He was afraid of them, and, ironically, so was I. His wild mom had influenced him, because she was always out with a different guy every night. He’d act like he wasn’t hurt that she wasn’t around, that he was above it all. But since his earliest years, he’d never be able to get enough female attention. As hard as he’d try, he couldn’t date enough, love enough or fuck enough to be satisfied. While we were in high school, I sensed that he kind of liked me. But I always felt safer staying in the friend zone with him. I think he did too.

He hung out with me in the treehouse, and eventually Dad stopped yelling. Then the house lights shut off and everything was quiet. That night, before I drifted off to sleep up in the treehouse, I felt the slightest brush of Jerry’s lips on my cheek. He was stealing a quick kiss! But I pretended to be asleep, because that was easier than talking about it and I was a coward.

He backed away. And we slept side by side up there.

The next morning, I heard a shotgun fire below the tree. It sounded as though the earth was exploding under us. Jerry and I scrambled to our feet as I heard Dad’s boots slowly creaking up each rung of the ladder. Dad’s bloodshot eyes, greasy hair and an expression smeared with contempt framed in the doorway, startled me with his intrusion. The treehouse was my private spot, something all my own. Dad had never crossed into that space before.

“You little whore!” he shouted at me.

The sickening sweet aroma of whiskey on his breath assaulted my senses, competing with the mildew stench of the rug inside the treehouse. I thought I was going to be sick.

“We didn’t do anything!” I hollered.

“You won’t talk back to me! Get on down here!” He climbed back down, and I knew what was coming.

I’d grown a lot taller over the summer, but his yelling still made me feel like a vulnerable little girl. I went down the ladder first. I knew that Dad would be so distracted with me, he’d leave Jerry alone or at least give him enough time to run away.

When I landed on the grass, I was surprised that I was face-to-face with Dad, a man who had always loomed over me like a dark shadow. When he raised his hand to slap me, I stepped back. My survival instincts awoke, and I was exhilarated by a sense of my own power.

“The next time you hit me,” I said, “I’m going to hit you back.” My face was stone, but my heart was pounding.

I could see Jerry on the bottom rung of the ladder, giving me a thumbs-up before racing across the field.

Dad turned away, headed toward the house, muttering obscenities. But that was the last time he ever raised his hand to me.

Adrienne

Jerry kept trying to start a rock band out of his garage. Since his mother was hardly ever home and no one knew where his dad was, he could spend hours doing drugs and God knows what and nobody would’ve known about it. That’s why I liked going over to his house.

The trouble with starting a band in a small town in central Florida was that it was hard to find enough people our age who wanted to be in a band. And no one from the big cities was going to move to our dinky-ass town to play in a yet-to-be-discovered band. So Jerry had his work cut out for him.

Knowing that I didn’t play an instrument didn’t stop him from asking me to join up, all the way until graduation. I’ll admit I didn’t take him seriously. Starting a band, to me, was the same as when five-year-olds say they want to be astronauts when they grow up. No one really believes you’re going off to NASA right after kindergarten.

The summer after our senior year was hard, mostly because Jerry had no intention of going to college. He resented anyone, including me, who was college-bound.

“You’re going to be one of them,” he teased, his legs flopping off the end of my double bed.

“Huh?”

“Those kids who go off to college, then come back all into making money and not giving a shit about their old friends anymore.” I think he was disappointed, watching me pack, because he’d been certain I’d never go to college.

“My dad is basically throwing me out of the house,” I replied as I threw my stuff into a suitcase.

“You could run away.” Jerry’s bright blue eyes lit up with possibilities. “We could run away and start a band!” He was a lovable teddy bear. In that moment, I thought of how some chick was going to fall hard for him someday.

I shook my head before diving to my knees and unhooking the wires of my stereo. It was a monstrosity, extra eighties-style bulky with gigantic speakers, one of which was slightly ripped. I loved it especially. I loved things that weren’t perfect, things that had tears or scars or some obvious flaw.

He crossed his arms, leaning against my bedroom doorframe. “You do everything Daddy says?”

He knew I’d hate him for that. “Fuck you,” I spat.

“Fuck you!”

I stood up, still holding a disconnected wire. “Get out,” I said. “And don’t bother coming back. I mean it.”

Jerry slouched away; I could hear his torn sneakers shuffling along our cigarette-stained carpet all the way to the screen door, which cracked loudly against the frame behind him. I couldn’t believe it. My best friend was out of my life forever. He knew how to hurt me, though. Say anything about my dad back then and I would’ve slugged you.

When I’d talked to my dad about college, I wasn’t excited about going. I wasn’t a brain; I was more the slacker in the back row who made fun of the teacher’s lisp or hairstyle. But Dad was all about how I’d have to get some shit job in town if I didn’t go to school, and that didn’t sound very appealing. It was also a chance to get away from him. His drinking was only getting worse. I didn’t want to stick around and see how bad his outbursts were going to be. I’d already had my head pushed into the sink where it hovered just above the garbage disposal that he’d switched on. That was one of many childhood memories I could’ve done without.

So I packed up the Camaro to head off to FSU. Dad gave me the car reluctantly. He didn’t trust his truck and was afraid I’d get stranded somewhere and “God knows what” would happen to me. He was a strange contradiction of caring about my welfare when he was sober and doing everything he could to destroy me when he was drunk. I was living with Jekyll and Hyde, and I was so sick of it. So tired. So ready to just let go. If there was a steep cliff, I wanted to jump off and be free—figuratively, of course. I was too stubborn to be suicidal. The very least I could do was to stick around, if only to piss him off.

Adrienne

I think Dad’s drinking got worse after Grandma, his mother, died. She was the main reason I went to college, something she’d told me the last time I saw her. She was in her eighties, somewhere in the middle, when, if you age just a little more, you’re flirting with ninety. She didn’t drive, so a friend of hers from the retirement village brought her. The driver was a little old lady who could barely see over the wheel. At first I assumed it was one of Dad’s drinking buddies, pulling up in an old tan Buick. I’d never seen the car before, but a lot of his friends drove older cars, mostly Chevys. I remember thinking it was odd how the car didn’t turn in our driveway. It seemed to hesitate a minute on the street, then crawled closer, idling at the curb near the mailbox. This frail little lady with bluish hair struggled to get out, and, leaning heavily on a cane, hobbled over the gravel drive to see me. I’d been hanging out at the treehouse and was about to go inside the main house when I saw her.

“Muffin,” she said.

I would’ve punched anyone else for calling me that. But that was her word for me since I was little. She played the piano and harmonica, and we’d pick out her favorite tunes when I was a kid. They were all songs from her generation, though some were actually from the 1970s. She liked songs from The Godfather. That’s what I remembered most. Her favorite was “Love Said Goodbye.” Years later, when I thought of that song I realized the melody was so incredibly sad. But I associated it with her, so it didn’t dig as deeply or hurt as much…until later.

Anyway, her name was Ruby. All her siblings were named after gemstones. She was the last surviving family member. There was Ruby, Pearl, Jade and Amber. Every time she saw me she’d remind me how each one died: Pearl got cancer, Jade got a different cancer, and Amber had something wrong with her spleen which didn’t show up on an X-ray. I knew each story by heart.

“Muffin,” she called, her voice a little stronger.

“Grandma?” I could almost hear the soundtrack of “Love Said Goodbye” in my head. “Where you been?”

I was fifteen, and I didn’t understand why Grandma hadn’t been by in what seemed like forever. She’d visited briefly shortly after my mom took off. But I hadn’t seen or heard from her since then.

“Oh, doin’ this and that.” She smiled tiredly under the strong Florida sun. “I’m livin’ at Crestwood Village. I’ll give you the number.” She smiled at me.

Later I’d understand that she’d come to check out how Dad was doing. When she came inside the house, he was still asleep at noon on Saturday. He’d slept in his clothes on the living room couch, so I couldn’t watch TV ’cause he’d yell if I woke him up. When I got older, I’d try to move him into his own bedroom at night. I think that’s where I got my sculpted biceps.

“Your daddy home?” Ruby asked in a slight Southern accent. She was originally from South Carolina but had been living in Florida most of her adult life.

“Yeah.” I pointed to the lump in an undershirt lying on the pea-green, nubby couch that belonged on The Brady Bunch.

Grandma had looked around, took it all in and made her judgment. “This place is a mess.”

“Yeah. If I didn’t do the dishes every night and throw out the beer cans, it would stink a lot worse, believe me.”

“Beer,” she sighed. “Do you know that roaches are attracted to the scent of beer?”

“No.” I glanced around, making sure I’d gotten all the cans and bottles. It looked like I had. It seemed as though I’d spent most of my life cleaning up after Dad’s shit.

“If he wasn’t my son,” she murmured. “I’d call Social Services.”

“Huh?”

“You in school?”

I nodded.

“You gettin’ out of here soon?”

“After high school, I guess.” I shrugged.

It was an odd scene, she and I in the dim blue light of the kitchen, keeping our voices low so as not to wake the sleeping bear on the couch. It had gotten so tired-looking and dirty, that couch. Before I knew it, Grandma turned and headed back out toward the waiting Buick.

“Hey, wait!” I called after her, following her down the gravel drive. “Are you comin’ back?”

She turned around, raised my chin and gave me a smile. “I was told I’m kinda sick, so I can’t make trips like this anymore. You got your license yet?”

“Nuh-uh. I’ll get a permit this year.”

“When you get your license, come see me at Crestwood.” She made sure I had the address. Before she got in the car, we stood on the quiet street, and she looked at me with piercing brown eyes. “You get out of here when you can, and don’t look back. Okay? Don’t look back.”

I squinted at her, a kid who didn’t know what Grandma was trying to say. In my mind, she was this old person who always told weird stories about people’s health and deaths and she could’ve meant anything. Only years later did I get it. I finally got what she meant.

By the time I got my license the next year, Grandma had died.

Laetitia V –

I couldn’t wait for the launch of ‘In her eyes’ – the sequel to Hurricane Days, which moved me in so many ways. Renée Lukas did not disappoint. If you haven’t read Hurricane Days, I highly recommend buying both books immediately, as you will be eager to absorb every word in record time. Besides this amazing love story, Ms Lukas’ refreshingly different way of story-telling (through the eyes of the main characters respectively), kept me glued to the pages, wishing there were more!