Stacy Lynn Miller discusses her experiences with stuttering, being an oddball, and her new novel Beyond the Smoke

Lazy. Shy. Quiet.

My doctor, teacher, and parents used those words to describe me through kindergarten because I refused to speak but a few words, preferring to let my older siblings do my talking for me. I wasn’t lazy, as the pediatrician declared to my mother when I was two. I had energy to spare. Nor was I shy, as my teacher wrote on my report card when I was five. I made friends and played with others, though silently. My parents knew why I was quiet but never pressed the issue after I refused to discuss it.

I was different. Not because I was short when others were tall or of average height. Nor because I wanted to dress in jeans and t-shirts when most girls dressed in bows and ruffles. I accepted being different in those ways because I wasn’t alone. My best friend the following year was only an inch taller and dressed a lot like me. Our tastes were similar, and we played with Barbies mostly in silence, just the way I liked it. We were the same except for one thing. She spoke perfectly, but I couldn’t pronounce the letter “R” and had a severe stutter. The great thing was that neither mattered to her.

Strangely, I never stuttered while singing or talking to myself. I knew I had it in me to speak smoothly, but once I opened my mouth in front of someone…anyone…the words logjammed. The only exception was when I was spitting mad. Then, the words flowed freely. Knowing I could do better made me a mixed bag of anger, shame, and low self-esteem because I was normal, yet I wasn’t. Compounding my predicament, no one I knew had a problem remotely like mine, making me the oddball in a fluent world. On bad days, my coping mechanism consisted of holing up in my room, often to cry into my pillow. Then came the soul-crushing moment.

On the first day of third grade, the teacher announced she would call the roll in alphabetical order by last name. Each student then had to introduce themself to the class and tell what they did during summer vacation. My mother had taught me to always obey, so the corner the teacher had painted me in made every inch of my skin tingle with anxiety.

As a Waren—I wasn’t Stacy Lynn Miller yet—I realized I’d be one of the last ones called. Each passing minute made me more nauseous than the last, and my heart almost beat out of my chest when she hit the T’s. I agonized through twenty-eight introductions until the teacher worked her way to me. Ready to throw up, I thankfully held down breakfast when I opened my mouth, but then my words jammed. I repeated sounds and blocked on my last name. No matter how hard I tried, I couldn’t get the word out.

The ensuing laughter and mimicking were embarrassing enough, but the crushing blow came when the teacher said, “Your last name is Warren,” as if I didn’t know it. She not only mispronounced my family name, but she also set off a volcano of anger that earned me the honor of being the first student of the school year to be sent to the principal’s office. That outburst changed my life.

The vice-principal, whom I would later learn had a son who stuttered, recognized my speech pattern after asking my name. A week later, he’d arranged for the school district’s speech therapist to work with me. After learning to curl my tongue within another week, I was pronouncing my R’s so proficiently that I drove my mother crazy by reciting every “R” word I could think of until it was bedtime. Mom said I spoke more to her that night than I had all year.

Regrettably, the therapist had no magic bullet for stuttering as she did for pronouncing Rs. Speech pacing, breath control, relaxation, and word substitution marginally improved my stutter but never made it go away. Though, the therapist reassured me that stuttering affected seventy million people and that I was in good company with the likes of Winston Churchill, Jimmy Stewart, and Marilyn Monroe. Knowing I wasn’t alone gave me some encouragement.

Most childhood stutterers outgrow their speech impediment before their teen years. That never happened for me, so working harder became my mantra. Work hard at speaking up even when my anxiety went into overdrive. Work hard at making my stutter less noticeable. Work hard at not letting the uncaring and unthinking who made fun of me get to me. Work hard at making myself so good at school and everything I did that no one would assume my speech meant I was stupid or inept.

Overachiever. Go-getter. Detailed-oriented.

My teachers, coaches, teammates, coworkers, family, and friends have used those words to describe me since my teenage years. My stutter is now less prominent. I don’t shy away from conversation unless I’m fangirling over someone I admire. I recognize my limitations, such as performing author readings. I do well with recordings, but in-person events are still beyond my comfort zone. When someone hits a soft spot, like finishing my sentence or making an insensitive comment, I let them know how they made me feel. As far as achieving, I’ve met almost every goal I’ve set for myself, including becoming a published author.

If there’s one thing my stutter journey has taught me, it’s that most limitations can be overcome by hard work. This early childhood lesson prepared me well for future trauma, health scares, and new disabilities. I learned to compartmentalize defeating emotion and focus on what I needed to do to push forward. I may not overcome my stumbling block, but at a minimum, I’m able to find a way around it. Now, let’s see if I can meet my next goal of having ten books published in five years.

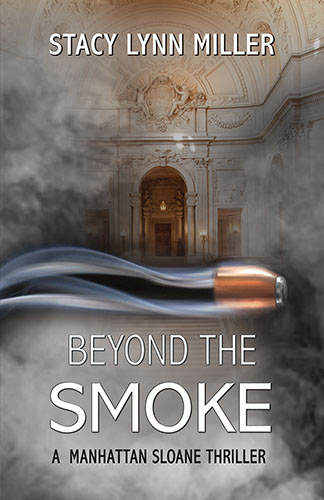

My next release is this July. Beyond the Smoke is the third installment of my Manhattan Sloane series. In this romantic mystery, find out if Sloane gets her happily ever after of if old flames and new secrets get in the way.

For more information on stuttering, visit The Stuttering Foundation. Here are three tips from Stacy Lynn Miller for what to do when encountering a person who stutters:

- Don’t make remarks like “Slow down, “Relax,” or “Take a breath.” Simplistic advice without understanding their coping routine can be demeaning.

- Try not to finish their sentence. Doing so will undercut their effort to communicate at their own pace.

- Make natural eye contact and wait patiently until they’re finished. Doing so will reassure them that you are listening to what they say, not how they say it.